Seriously ugly: here’s how Australia will look if the world heats by 3°C this century

Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, The University of Queensland and Lesley Hughes, Macquarie University

Imagine, for a moment, a different kind of Australia. One where bushfires on the catastrophic scale of Black Summer happen almost every year. One where 50℃ days in Sydney and Melbourne are common. Where storms and flooding have violently reshaped our coastlines, and unique ecosystems have been damaged beyond recognition – including the Great Barrier Reef, which no longer exists.

Frighteningly, this is not an imaginary future dystopia. It’s a scientific projection of Australia under 3℃ of global warming – a future we must both strenuously try to avoid, but also prepare for.

The sum of current commitments under the Paris climate accord puts Earth on track for 3℃ of warming this century. Research released today by the Australian Academy of Science explores this scenario in detail.

The report, which we co-authored with colleagues, lays out the potential damage to Australia. Unless the world changes course and dramatically curbs greenhouse gas emissions, this is how bad it could get.

A spotlight on the damage

Nations signed up to the Paris Agreement collectively aim to limit global warming to well below 2℃ this century and to pursue efforts to limit temperature increase to 1.5℃. But on current emissions-reduction pledges, global temperatures are expected to far exceed these goals, reaching 2.9℃ by 2100.

Australia is the driest inhabited continent, and already has a highly variable climate of “droughts and flooding rains”. This is why of all developed nations, Australia has been identified as one of the most vulnerable to climate change.

The damage is already evident. Since records began in 1910, Australia’s average surface temperature has warmed by 1.4℃, and its open ocean areas have warmed by 1℃. Extreme events – such as storms, droughts, bushfires, heatwaves and floods – are becoming more frequent and severe.

Today’s report brings together multiple lines of evidence such as computer modelling, observed changes and historical paleoclimate studies. It gives a picture of the damage that’s already occurred, and what Australia should expect next. It shines a spotlight on four sectors: ecosystems, food production, cities and towns, and health and well-being.

In all these areas, we found the impacts of climate change are profound and accelerating rapidly.

Read more:

Yes, Australia is a land of flooding rains. But climate change could be making it worse

Richard Wainwright/AAP

1. Ecosystems

Australia’s natural resources are directly linked to our well-being, culture and economic prosperity. Warming and changes in climate have already eroded the services ecosystems provide, and affected thousands of species.

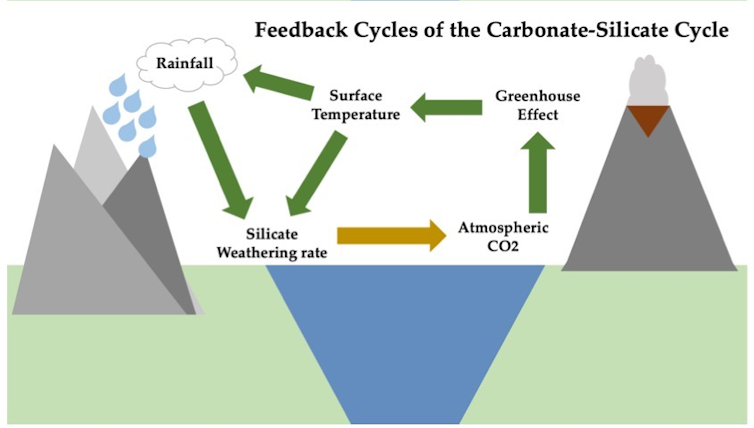

The problems extend to the ocean, which is steadily warming. Heat stress is bleaching and killing corals, and severely damaging crucial habitats such as kelp forests and seagrass meadows. As oceans absorb carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere, seawater is reaching record acidity levels, harming marine food webs, fisheries and aquaculture.

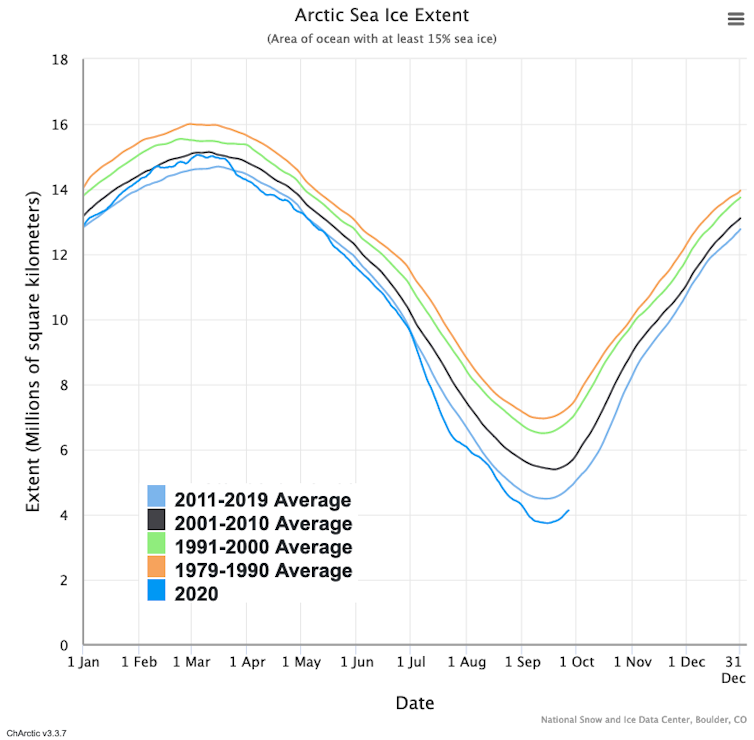

At 3℃ of global warming by 2100, oceans are projected to absorb five times more heat than the observed amount accumulated since 1970. Being far more acidic than today, ocean oxygen levels will decline at ever-shallower depths, affecting the distribution and abundance of marine life everywhere. At 1.5-2℃ warming, the complete loss of coral reefs is very likely.

Read more:

The oceans are changing too fast for marine life to keep up

Shutterstock

Under 3℃ warming, global sea levels are projected to rise 40-80 centimetres, and by many more metres over coming centuries. Rising sea levels are already inundating low-lying coastal areas, and saltwater is intruding into freshwater wetlands. This leads to coastal erosion that amplifies storm impacts and affects both ecosystems and people.

Land and freshwater environments have been damaged by drought, fire, extreme heatwaves, invasive species and disease. An estimated 3 billion vertebrate animals were killed or displaced in the Black Summer bushfires. Some 24 million hectares burned, including 80% of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area and 50% of Gondwana rainforests. At 3℃ of warming, the number of extreme fire days could double.

Some species are shifting to cooler latitudes or higher elevations. But most will struggle to keep up with the unprecedented rate of warming. Critical thresholds in many natural systems are likely to be exceeded as global warming reaches 1.5℃. At 2℃ and beyond, we’re likely to see the complete loss of coral reefs, and inundation of iconic ecosystems such as the World Heritage-listed Kakadu National Park.

At 3℃ of global warming, Australia’s present-day ecological systems would be unrecognisable. The first documented climate-related global extinction of a mammal, the Bramble Cay melomys from the Torres Strait, is highly unlikely to be the last. Climate change is predicted to increase extinction rates by several orders of magnitude.

Degradation of Australia’s unique ecosystems will harm the tourism and recreation industries, as well as our food security, health and culture.

There are ways to reduce the climate risk for ecosystems – many of which also benefit humans. For example, preserving and restoring mangroves protects our coasts from storms, increases carbon storage and retains fisheries habitat.

Shutterstock

2. Food production

Australian agriculture and food security already face significant risks from droughts, heatwaves, fires, floods and invasive species. At 2℃ or more of global warming, rainfall will decline and droughts in areas such as southeastern and southwestern Australia will intensify. This will reduce water availability for irrigated agriculture and increase water prices.

Heat stress affects livestock welfare, reproduction and production. Projected temperature and humidity changes suggest livestock will experience many more heat stress days each year. More frequent storms and heavy rainfall are likely to worsen erosion on grazing land and may lead to livestock loss from flooding.

Heat stress and reduced water availability will also make farms less profitable. A 3℃ global temperature increase would reduce yields of key crops by between 5% and 50%. Significant reductions are expected in oil seeds (35%), wheat (18%) and fruits and vegetables (14%).

Climate change also threatens forestry in hotter, drier regions such as southwestern Australia. There, the industry faces increased fire risks, changed rainfall patterns and growing pest populations. In cooler regions such as Tasmania and Gippsland, forestry production may increase as the climate warms. Existing plantations would change substantially under 3℃ warming.

As ocean waters warm, distributions and stock levels of commercial fish species are continuing to change. This will curb profitability. Many aquaculture fisheries may fundamentally change, relocate or cease to exist.

These changes may cause fisheries workers to suffer unemployment, mental health issues (potentially leading to suicides) and other problems. Strategic planning to create new business opportunities in these regions may reduce these risks.

Read more:

Australia’s farmers want more climate action – and they’re starting in their own (huge) backyards

Shutterstock

3. Cities and towns

Almost 90% of Australians live in cities and towns and will experience climate change in urban environments.

Under a sea level rise of 1 metre by the end of the century – a level considered plausible by federal officials – between 160,000 and 250,000 Australian properties and infrastructure are at risk of coastal flooding.

Strategies to manage the risk include less construction in high-risk areas, and protecting coastal land with sea walls, sand dunes and mangroves. But some coastal areas may have to be abandoned.

Extreme heat, bushfires and storms put strain on power stations and infrastructure. At the same time, more energy is needed for increased air conditioning use. Much of Australia’s electricity generation relies on ageing and unreliable coal-fired power stations. Extreme weather can also disrupt and damage the oil and gas industries. Diversifying energy sources and improving infrastructure will be important to ensure reliable energy supplies.

The insurance and financial sector is becoming increasingly aware of climate risk and exposure. Insurance firms face increased claims due to climate-related disasters including floods, cyclones and mega-fires. Under some scenarios, one in every 19 property owners face unaffordable insurance premiums by 2030. A 3℃ world would render many more properties and businesses uninsurable.

Cities and towns, however, can be part of the climate solution. High-density urban living leads to a lower per capita greenhouse gas emission “footprint”. Also, innovative solutions are easier to implement in urban environments.

Passive cooling techniques, such as incorporating more plants and street trees during planning, can reduce city temperatures. But these strategies may require changes to stormwater management and can take time to work.

Read more:

When climate change and other emergencies threaten where we live, how will we manage our retreat?

David Moir/ AAP

4. Human health and well-being

A 3℃ world threatens human health, livelihoods and communities. The elderly, young, unwell, and those from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds are at most risk.

Heatwaves on land and sea are becoming longer, more frequent and severe. For example, at 3℃ of global warming, heatwaves in Queensland would happen as often as seven times a year, lasting 16 days on average. These cause physiological heat stress and worsen existing medical conditions.

Bushfire-related health impacts are increasing, causing deaths and exacerbating pre-existing conditions such as heart and lung disease. Tragically, we saw this unfold during Black Summer. These extreme conditions will increase at 2℃ and further at 3℃, causing direct and indirect physical and mental health issues.

Under 3℃ warming, climate damage to businesses will likely to lead to increased unemployment and possibly higher suicide rates, mental health issues and health issues relating to heat stress.

At 3°C global warming, many locations in Australia would be very difficult to inhabit due to projected water shortages.

As weather patterns change, transmission of some infectious diseases, such as Ross River virus, will become more intense. “Tropical” diseases may spread to more temperate areas across Australia.

Strategies exist to help mitigate these effects. They include improving early warning systems for extreme weather events and boosting the climate resilience of health services. Nature-based solutions, such as increasing green spaces in urban areas, will also help.

Read more:

How does bushfire smoke affect our health? 6 things you need to know

Lukas Coch/AAP

How to avoid catastrophe

The report acknowledges that limiting global temperatures to 1.5℃ this century is now extremely difficult. Achieving net-zero global emissions by 2050 is the absolute minimum required to to avoid the worst climate impacts.

Australia is well positioned to contribute to this global challenge. We have a well-developed industrial base, skilled workforce and vast sources of renewable energy.

But Australia must also pursue far more substantial emissions reduction. Under the Paris deal, we’ve pledged to reduce emissions by 26-28% between 2005 and 2030. Given the multiple and accelerating climate threats Australia faces, we must scale up this pledge. We must also display the international leadership and collaboration required to set Earth on a safer climate trajectory.

Our report recommends Australia immediately do the following:

- join global leaders in increasing actions to urgently tackle and solve climate change

- develop strategies to meet the challenges of extreme events that are increasing in intensity, frequency and scale

- improve our understanding of climate impacts, including tipping points and the compounding effects of multiple stressors at global warming of 2℃ or more

- systematically explore how food production and supply systems should prepare for climate change

- better understand the impacts and risks of climate change for the health of Australians

- introduce policies to deliver deep and rapid cuts in emissions across the economy

- scale up the development and implementation of low- to zero-emissions technologies

- review Australia’s capacity and flexibility to take up innovations and technology breakthroughs for transitioning to a low-emissions future

- develop a better understanding of climate solutions through dialogue with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – particularly strategies that helped people manage Australian ecosystems for tens of thousands of years

- continue to build adaptation strategies and greater commitment for meeting the challenges of change already in the climate system.

We don’t have much time to avert catastrophe. This decade must be transformational, and one where we choose a safer future.

The report upon which this article is based, The Risks to Australia of a 3°C Warmer World, was authored and reviewed by 21 experts.

Read more:

Climate crisis: keeping hope of 1.5°C limit alive is vital to spurring global action

![]()

Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, Professor, The University of Queensland and Lesley Hughes, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.