Revealed: UK ‘double counting’ £500m of aid for war-torn countries as climate finance

Original article by JOSH GABBATISS republished from Carbon Brief under a CC license.

The UK government has reclassified nearly £500m of aid for war-torn and impoverished countries as “climate finance”, in a bid to meet its international commitments under the Paris Agreement.

This follows reports that the UK’s pledge to spend £11.6bn on climate aid between 2021-22 and 2025-26 is slipping out of reach, due to government cuts.

A freedom-of-information (FOI) request by Carbon Brief reveals how, after the reclassification, money for humanitarian work in nations including Afghanistan, Yemen and Somalia is now being double-counted as climate finance to help the UK hit its goal.

The projects being double-counted include work to provide food and basic necessities that have no explicit link to climate action, Carbon Brief’s analysis reveals. Some of their internal reports even state clearly that they are not climate-finance projects.

This is part of a wider revision of climate-finance accounting, introduced by the government in 2023 to ensure the UK achieves its £11.6bn target.

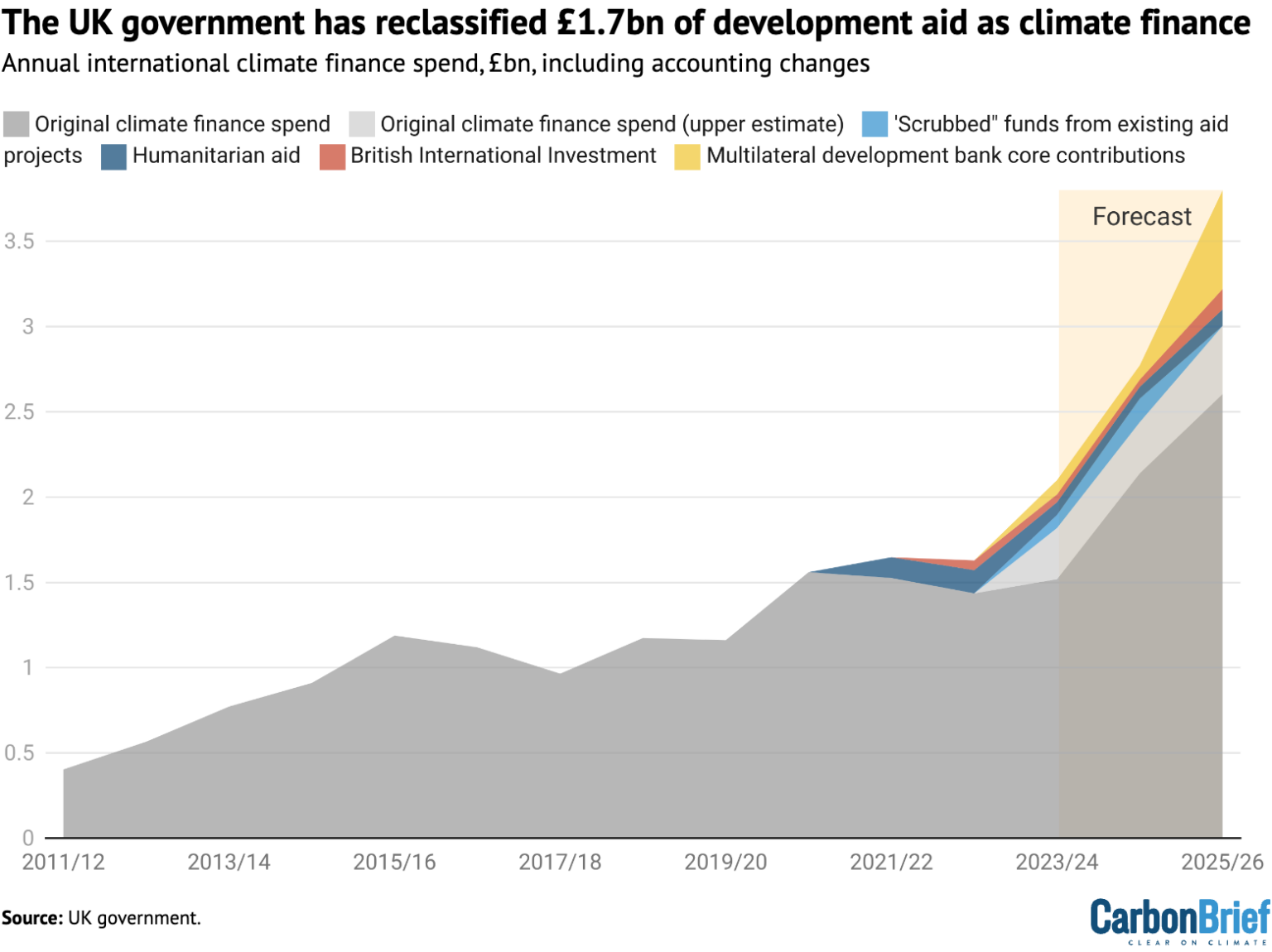

By redefining existing funds pegged for development banks, investment in foreign businesses and humanitarian aid as “climate finance”, the government expects to add £1.72bn to its total.

Experts tell Carbon Brief it is “problematic” and “unjust” to relabel existing funds as climate finance rather than providing new money. One says the UK could meet its target, at least in part, by “double counting development and climate finance”.

The chair of the Least Developed Countries (LDC) group at UN climate talks says the UK’s actions are a “clear deviation from the path to climate justice”.

‘Moving the goalposts’

The UK government has committed to spending £11.6bn on international climate finance (ICF) between 2021-22 and 2025-26. This is the nation’s contribution to climate action in developing countries, which it is obliged to provide under the Paris Agreement.

Developed countries, such as the UK, have committed to sending “new and additional” climate finance to developing countries. This is generally interpreted as spending extra money on top of existing foreign aid.

The UK government itself has described the £11.6bn goal as “dedicated ring-fenced funding that is distinguishable from non-climate [aid]”.

However, reports began to emerge in 2023 that the government was not on track to meet its target.

Experts attributed this to the government cutting its overall foreign aid budget. In November 2020, the government suspended a target to give 0.7% of national income as overseas aid – reducing it to 0.5% as a “temporary measure”.

The government is also spending more of the remaining funds on supporting refugees within the UK. The latest figures show that in 2023, the UK spent more of its aid budget on supporting asylum seekers and refugees in the country than on overseas projects.

In order to remain on track for the £11.6bn goal, development minister Andrew Mitchell announced in October 2023 that the government was changing the way it calculated ICF spending.

This immediately sparked concerns that the government was inflating its climate-finance figures without providing any new aid money for developing countries. Mitchell provided limited details of how the government was getting its target back on track.

More information came in a report released in February by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI). It concluded that, by “moving the goalposts”, the government had reclassified £1.72bn of spending as climate finance between 2021-22 and 2025-26.

This figure includes four tranches of funding that had not previously been considered ICF:

- £746m from assuming that a share of the “core” funding the UK gives to the World Bank and other multilateral development banks (MDBs) will be assigned to climate-related projects.

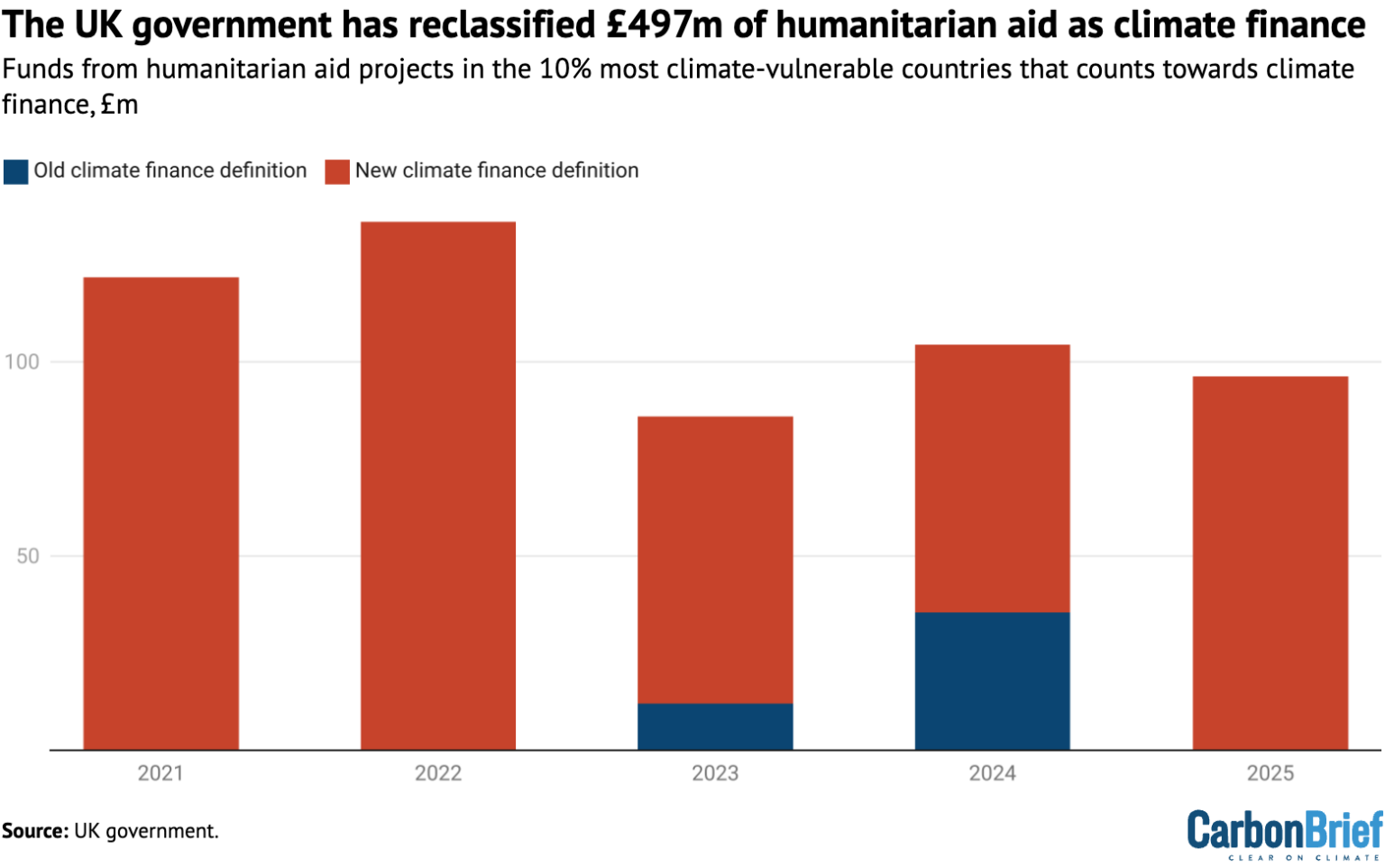

- £497m from automatically labelling 30% of the humanitarian aid spent in the 10% of countries that are most vulnerable to climate change as ICF.

- An estimated £266m from defining more payments into British International Investment (BII), the UK’s overseas development finance institution, as ICF.

- £215m from civil servants “scrubbing” the aid portfolio – namely, going back over existing projects and adding any climate-relevant funding they had previously missed.

The figures cited by ICAI are based on unpublished government analysis, which Carbon Brief has now obtained via FOI.

The analysis includes the annual contributions each of these sources are expected to provide over the period from 2021-22 to 2025-26, which can be seen in the coloured sections of the chart below.

As the chart indicates, even with the methodology changes, the £11.6bn target is still “backloaded”, with a significant uptick in ICF spending required beyond 2023-24 to meet it.

ICAI notes that, since the government cut its aid spending from the UN-backed benchmark of 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income (GNI), “serious concerns remain over whether the heavily backloaded spending plan can be delivered”.

Core funding

The largest tranche of redefined ICF – some £740m – comes from the government starting to assume that a share of its “core” MDB funding counts as climate finance.

This is money that the UK government already hands to these organisations to distribute according to their own priorities, primarily through loans. None of this money has previously been counted by the UK government as ICF, even though some went towards climate action.

MDBs, including the World Bank, the African Development Bank (AfDB) and others have placed a growing emphasis on climate change in recent years. The World Bank, for example, has a target of spending 35% of its finance on climate-related projects.

Following the reclassification, the UK government will simply assume that 35% of the money it gives to the World Bank – some £495m of £1.4bn total due in 2025/26 – counts as ICF.

It will use a similar approach for its funding of other MDBs, with these changes adding a total of £740m to the amount of the UK’s aid spending that is classified as ICF.

This move will not result in the UK providing any new funds for climate action, as it was already planning on distributing this money. In fact, the government has cut its spending on MDBs in recent years, due to the overall cut in the UK’s foreign aid budget.

Humanitarian aid

The second-largest tranche of newly reclassified climate finance is from projects in climate-vulnerable countries, an additional £497m of which is being counted as ICF.

The government dataset obtained by Carbon Brief via FOI reveals the 28 humanitarian projects and five more general, country-specific funds that will contribute to this additional £497m.

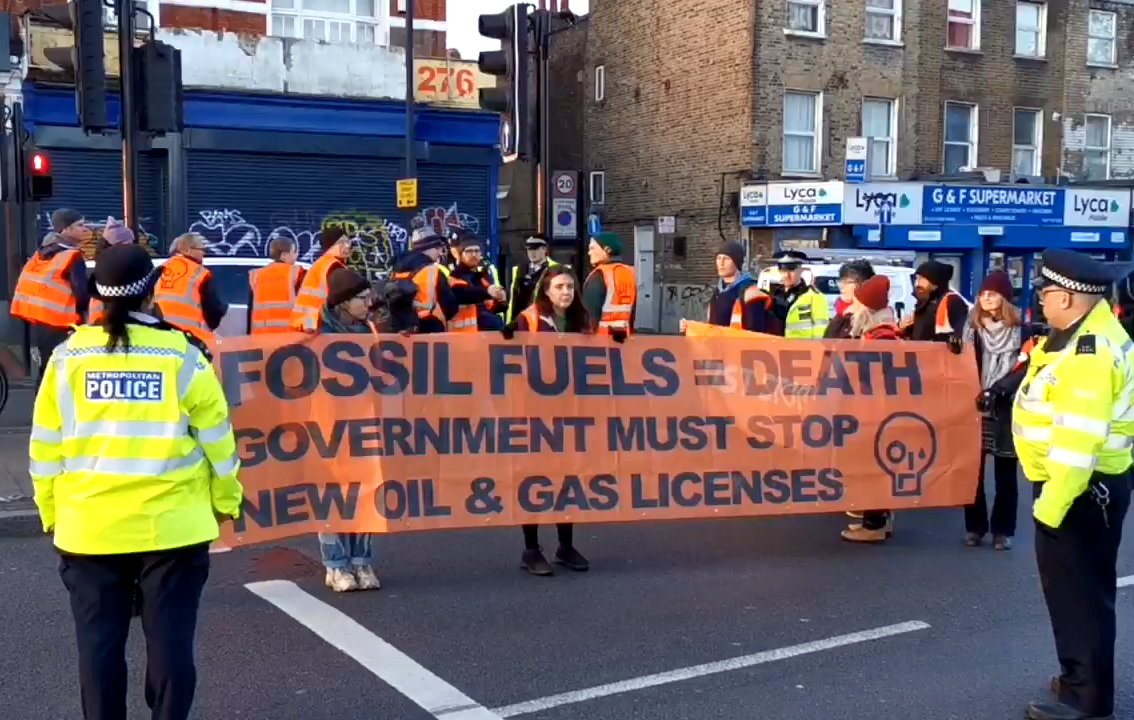

The projects are based in some of the poorest and most war-torn countries in the world – Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Somalia, Sudan, Uganda, Yemen and Zimbabwe.

They largely focus on essential provisions, such as food and basic infrastructure.

Prior to the recent changes, these programmes would have contributed just £47.5m to ICF, according to the government data released to Carbon Brief.

By automatically counting 30% of their spend as ICF, this figure has now multiplied more than 10 times. The chart below shows, in red, these additional ICF funds.

For the 23 of the 28 projects with documentation available online, Carbon Brief assessed the relevant sections of their “business case and summary” documents for evidence that they were related to climate action.

Many of the project documents reference climate change and say they will provide climate benefits. For example, all four projects in Somalia, a nation that has faced devastating drought and floods in recent years, mention the importance of climate resilience in their work.

However, some of the projects explicitly state that they are not intended to provide climate-finance.

The summary document for the Assurance and Learning Programme (ALP) in Afghanistan, published in 2021, states: “The programme will not be eligible for ICF nor will it monitor ICF funded programmes.”

Similarly, the Congo Humanitarian, Resilience and Protection (CHRESP) Programme summary document, also published in 2021, notes “we do not anticipate that any of our programming under this programme will be eligible as ICF”.

Another project, titled Yemen: Access, Logistics, Liaison, and Accountability, will provide “few opportunities” to address climate change, according to the summary document. A further four project documents do not contain any reference to climate change.

Despite this, following the government’s reclassification, these seven projects will collectively contribute £166.9m of UK climate finance in the coming years.

Euan Ritchie, a senior development finance policy advisor at the thinktank Development Initiatives, says blanket approaches to assigning climate finance are “problematic”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Just because humanitarian aid is going to a country that is vulnerable to climate change doesn’t mean it addresses that vulnerability. And these projects have already been screened for their climate focus.”

He points to one of the projects, the Somalia Humanitarian and Resilience Programme, as an example. Ritchie says, based on International Aid Transparency Initiative data, that officials had already decided around 12% of this programme’s spending was ICF, and asks:

“So what rationale is there for bumping it up to 30%? Were officials wrong the first time?”

Fatuma Hussein, a programme manager at the thinktank Power Shift Africa, tells Carbon Brief such an approach is “unfair and unjust” as it “risks conflating” the “distinct needs” of climate aid and other humanitarian objectives.

In its guidance for categorising what counts as climate finance, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee recommends scoring many humanitarian projects “zero”, indicating programmes that “generally do not qualify” as climate aid.

More private investment

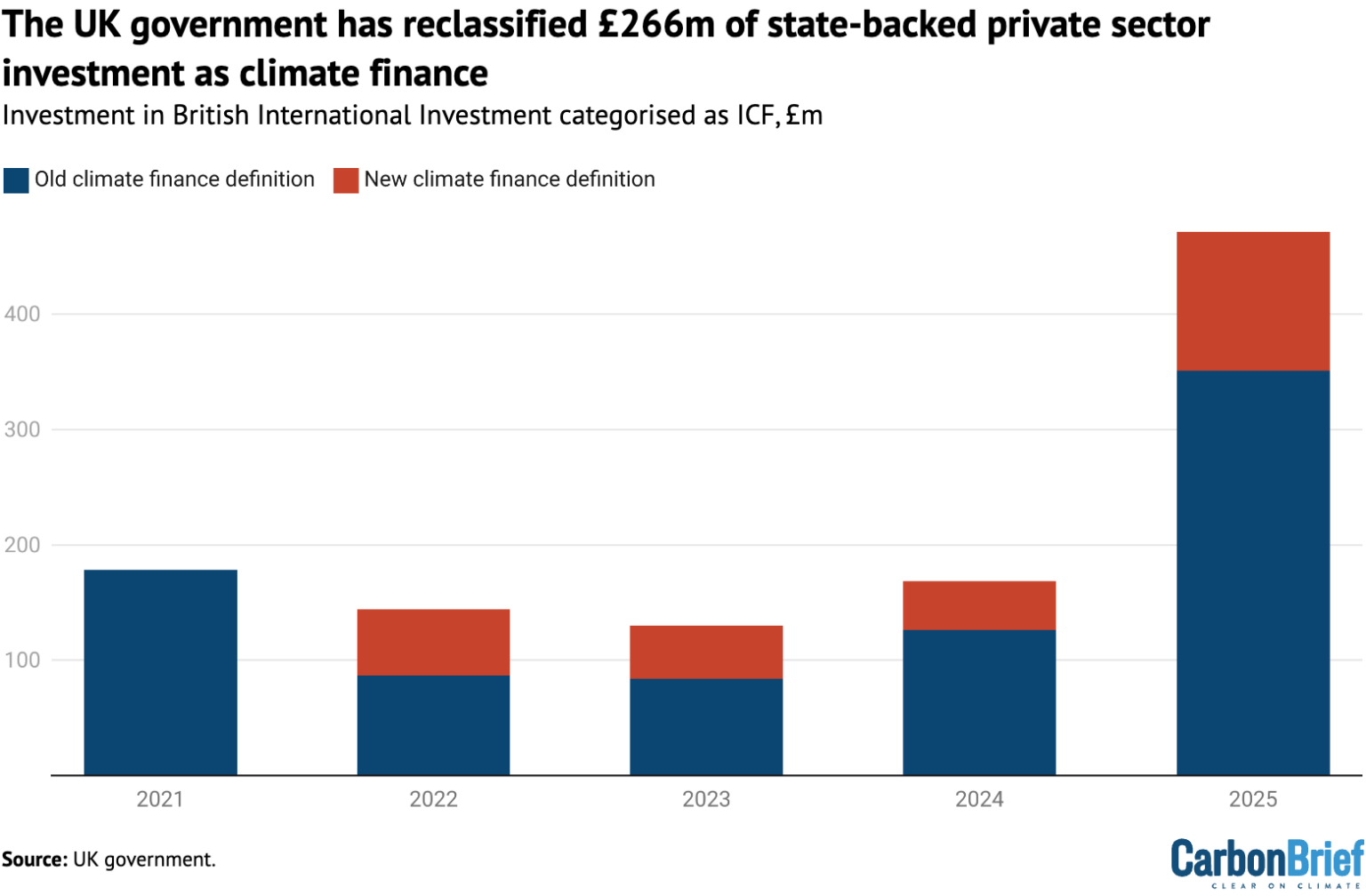

The third-largest tranche of reclassified development aid relates to state-backed private sector investment under British International Investment (BII).

The UK government will also now count more of its payments into BII as climate finance, amounting to around an extra £266m by 2025-26. Unlike aid spending, these are investments in the private sector and are expected to yield a financial return for the UK.

Previously, the government counted a fixed 30% of BII spending as climate finance. It now intends to include a higher percentage to reflect a growing focus on climate investments.

The new approach to BII investments assesses the share of each project that should count towards UK climate finance case-by-case, rather than using a blanket 30% share.

It will record 100% of investments in a programme covering the Philippines, Indonesia and other parts of south-east Asia as ICF, as part of the government’s “Indo-Pacific tilt”. Investments in other regions also contribute a higher share of ICF – rising as high as 46% in 2022-23.

The chart below shows the extra BII investment money (red) that now counts as ICF.

The figure above shows that the government expects private sector investment via BII to play an increasingly large role in its climate finance in the future.

Many observers have expressed concerns about the government leaning more on private investment through BII to boost its ICF spending.

A report last year by the parliamentary international development committee criticised BII’s investment in, among other things, fossil fuels and “high-net-worth individuals”.

BII prioritises loans and projects in middle-income nations where there is money to be made, rather than the nations that are most in need of climate finance.

ICAI highlighted this in its review of the UK’s climate finance commitments earlier this year, stating that private investment “is not always the most appropriate, realistic or preferred form of climate finance in the poorest and most fragile contexts”.

Not new, not additional

Developing countries will require trillions of dollars of investment in the coming years to meet their climate goals.

To help achieve this, developed countries, such as the UK, are expected to provide finance under the UN climate system that is “new and additional”. Discussions around a new climate finance goal will take centre stage this year at the COP29 climate summit in Baku.

Experts tell Carbon Brief that the UK government’s changes to its ICF undermine the notion that it is providing new, “ring-fenced” funding. Regarding the “arbitrary” labelling of humanitarian funds as ICF, Ritchie says:

“If the UK is counting a fixed share of projects as ICF it can no longer claim that ICF is distinguishable from non-climate [aid].”

Gideon Rabinowitz, director of policy and advocacy at the international development network Bond, tells Carbon Brief:

“The change of definition means they will be able to reach the target by spending less money than they would have done otherwise through double counting development and climate finance.”

Development NGOs say the best way for the UK to scale up its climate finance would be to return its foreign aid budget to 0.7% of GNI. However, with an election looming, neither the ruling Conservatives nor their Labour challengers have indicated a willingness to do this.

There will be considerable pressure on developed countries in the coming months to commit to providing plentiful, high-quality climate finance in the run up to COP29.

Evans Njewa, the chair of the LDC group, to which nearly all of the UK’s humanitarian aid ICF recipients belong, tells Carbon Brief:

“Reclassifying existing donor aid as climate finance is a clear deviation from the path to climate justice, and closing the finance gap cannot be achieved this way.”

Climate-finance reporting has been described as a “wild west”, with countries announcing figures based on vastly different definitions. This has led to nations counting money for coal, hotels and films in their totals, as there is no binding international standard to guide them.

The UK government noted last year that its changes are in line with other countries’ methods. But experts point out that the UK was previously viewed as setting a high standard for other countries to reach.

In contrast, the new approach “risks breeding cynicism and mistrust because you are going to find programmes that have very little to do with climate change, but end up being reported in the pot as climate finance”, Rabinowitz says.

Hussein agrees, telling Carbon Brief:

“This not only highlights the disparity between western countries’ rhetoric on climate finance and their actual financial commitments to developing countries but also risks undermining trust that underpins global climate action.”

She argues that nations should agree on common definitions and accounting methodologies for climate finance to ensure that governments cannot backslide as the UK has.

Responding to Carbon Brief’s questions about the government’s methodology changes, a spokesperson from the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) said:

“Since 2011, UK funding has helped more than 100 million people cope with the effects of climate change, given 70 million people access to clean energy and reduced or avoided over 86m tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions.

“The UK remains on track to meet the £11.6bn international climate finance commitment.”

Original article by JOSH GABBATISS republished from Carbon Brief under a CC license.