Why the Belief That Carbon Capture Technologies Can Work at Gigaton-Scale Is a Gigantic Gamble

Original article by Dana Drugmand republished from DeSmog.

Despite CCS’s track record of failure and glaring feasibility issues, petrostates are expected to use it as cover to dismiss fossil fuel phaseout at COP28.

With the start of the 28th annual United Nations climate summit, COP28, just two weeks away, a battle is brewing over the role of fossil fuels as nations try to stem the tide of climate change.

A “high ambition” coalition of nations such as France, Tuvalu, Ethiopia, and Ireland backed by climate scientists, climate and civil society organizations, and the UN Secretary General, are calling for commitments to phase out coal, oil, and gas. On the other hand, many oil and gas producing countries, supported by the politically potent fossil fuel lobby, are urging an approach that allows continued fossil fuel extraction – and even expansion – under the assumption that emissions mitigation technologies can largely eliminate the climate pollution of business-as-usual, emissions-intensive activities.

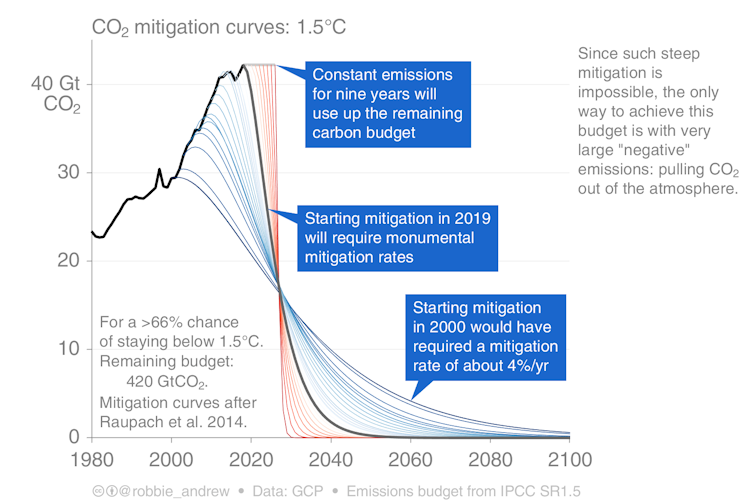

Now, a new report shows that fossil fuel production by 2030 is set to exceed the level that would be compatible with limiting warming to 1.5°C by more than 110 percent. A second just-released report reveals that to mitigate that growth, the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies would have to reach gigaton scale in less than 10 years, which might not be possible.

“That idea that we can build more fossil fuels but it’s ok because we can mitigate the emissions, or we’ll be able to pull carbon out of the air or out of the smokestacks, I think is incredibly dangerous,” Collin Rees, U.S. program manager at Oil Change International, said during a November 14 media briefing sponsored by a coalition called Gas Exports Today, which was convened by the Louisiana Bucket Brigade and held in advance of COP28.

In remarks delivered at the UN Climate Ambition Summit in September, COP28 president Sultan Al Jaber said that a “phase down,” not a “phase out,” of fossil fuels is what’s needed to combat climate change. He also referenced building “an energy system free of all unabated fossil fuels.” The term “unabated” has become a major reference in the climate diplomacy conversation in recent years, starting with COP26 in Glasgow where governments agreed to accelerate efforts “towards the phasedown of unabated coal power.” This language serves as a qualifier to suggest that fossil fuels can be rendered ‘clean’ through carbon capture and storage and engineered carbon dioxide removal, collectively termed “carbon management.”

While these technologies may seem promising in theory, in practice they face substantial constraints and challenges. The two new reports further underscore these limitations.

Governments around the world are planning to produce more than double the amount of fossil fuels in 2030 than is consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 °C, which is the more stringent objective of the Paris Agreement, according to the new Production Gap Report (PGR) 2023, produced by the UN Environment Program and the Stockholm Environment Institute, along with several other climate think tanks.

“There is overwhelming scientific evidence that we need to phase out all fossil fuels as rapidly as possible,” Ploy Achakulwisut, research fellow at the Stockholm Environment Institute and co-author of the Production Gap Report, said during the report’s virtual launch event on November 8. The report takes into account the significant risks and uncertainties around CCS and CDR, warning that the potential failure of these technologies to reach a climate-relevant scale necessitates an even more urgent phaseout of all fossil fuels. Given the feasibility concerns around scaling up carbon management technologies, the report urges governments to strive to phase out coal by 2040 and slash oil and gas production and use by three-quarters (from 2020 levels) by 2050 at a minimum.

Achakulwisut noted that even though the majority of modeled climate mitigation scenarios from the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report assume that large amounts of CCS and CDR facilities can be deployed successfully, there is little evidence to back this assumption. In fact, annual capacity from operating CCS projects resulting in dedicated storage currently amounts to less than 0.1 percent of global annual CO2 emissions, Achakulwisut said. When it comes to reducing overall global carbon emissions, she noted, CCS is not making a dent.

This is likely to be the case in 2030 too, with CCS deployment at that point expected to still not move the needle on lowering emissions. “Even if all CCS facilities planned and under development worldwide become operational,” the Production Gap report explains, “only around 0.25 [gigatons] of CO2 would be captured in 2030, less than 1% of 2022 global CO2 emissions.” The report refers to an International Energy Agency dataset which projects, as of March 2023, less than 350 million metric tons of CO2 capture capacity from all of the global CCS projects planned, under construction, and operational in 2030.

The International Energy Agency’s updated Net Zero roadmap report released in September references a slightly higher figure, saying that around 400 million metric tons of CO2 could be captured by 2030 if all planned CCS projects get built, which, the agency said, is still only 40 percent of the 1 gigaton-per-year capture capacity needed by 2030 in its net zero emissions scenario.

“There’s a huge range of evidence which is very clear that CCS and CDR will not be able to scale fast enough to make a meaningful contribution to cutting emissions this decade,” Neil Grant, climate and energy analyst at Climate Analytics, said during the report’s launch event. “And that means in this decade, the solution has to be reducing fossil fuel production and use.”

Carbon dioxide removal technologies, he added, “are very nascent.” Most existing direct air capture (DAC) operations are small-scale pilot projects. The world’s first commercial-scale DAC plant, called Orca and based in Iceland, has a capacity to capture up to 4,000 tons of CO2 per year – equivalent to the annual emissions of about 800 cars worldwide, or approximately three seconds worth of global CO2 emissions.

Is DAC Feasible?

Yet, significant government subsidies and investment are flowing into direct air capture, and plans to develop at least 130 DAC facilities are now underway. But according to a new briefing paper from the Center for International Environmental Law, even if all the planned DAC projects in the world get built and operate at full capacity, they would be capable of removing just 4.7 million metric tons of CO2 in 2030, equivalent to a mere 0.01 percent of current global energy sector emissions. Even assuming that DAC could eventually reach a massive scale, the enormous quantities of chemicals and energy inputs required to operate the machinery raises further feasibility and sustainability questions.

Essentially, the math just doesn’t add up in terms of the projected scale up of the carbon management sector in what experts say is the critical decade to curb planet-warming emissions by at least 50 percent. Experts say CCS and CDR would have to reach gigaton scale in less than 10 years, and there is no assurance that it will get there in time.

A new report from the Global CCS Institute, a pro-CCS think tank and advocacy group, actually affirms this. Although there has been momentum in policies, financing, and proposed projects in the carbon management sector, there is still a big, glaring question as to whether scaling up to the gigaton level by 2030 is even feasible, according to the Institute’s Global Status of CCS 2023 report released last week.

“The math also indicates that this past year’s impressive step-up still has us near the bottom of the staircase, so to speak, and that CCS must reach gigatonne per annum (Gtpa) scale in order to reach our emission goals,” Global CCS Institute CEO Jarad Daniels said in a media release accompanying the report.

Only a few dozen CCS facilities are currently operational at the global level, 14 of which are in the U.S., with a total capacity to capture and store 49 million metric tons of CO2, the report states. However, the total capacity is not the same as the amount actually captured and sequestered, as CCS facilities often do not operate at their maximum potential. When considering the additional energy required to power CCS operations, and given that the vast majority of existing projects use the captured CO2 to extract more oil and gas – a process called enhanced oil recovery – the net result is generally more, not less, greenhouse gas emissions.

As far as CCS projects that are proposed or “in the pipeline” as the report calls it, that number is 392 as of July this year. But as Daniels noted in the Institute’s report launch event on November 9, most of the facilities in development would be aiming to begin operating starting in 2030, at the earliest. There are many hurdles, such as permitting and securing financing, that projects have to overcome before they start capturing any carbon molecules. The lag time between when projects are announced and when they become operational is typically around seven years or more, the report says, acknowledging that “relatively few [new CCS projects] have yet advanced to operation.”

These delays have in the past been due, at least in part, to local opposition and unsuccessful community engagement, which have resulted in some project cancellations, according to the report. “Lack of community support, coupled with permitting challenges, has become a barrier for some early development stage CCS projects in the U.S.,” the report states.

Community opposition and public pushback to CCS projects, as DeSmog recently reported, appears to be growing across the U.S., and it demonstrates that “meaningful” community engagement rhetoric from CCS proponents does not often match the reality on the ground. One major proposed CCS infrastructure project in the U.S. – a 1,300-mile-long CO2 pipeline traversing five Midwestern states that was planned by a developer called Navigator CO2 Ventures – was canceled last month in the face of overwhelming grassroots opposition along with permitting challenges.

“Unmet Expectations”

The barriers and significant questions around the feasibility of CCS technologies to even scale up at any climate-relevant level are on top of an existing track record that, at best, is not very promising and at worst could be viewed as largely a failure. Analyses from DeSmog and from IEEFA, among others, show that most large-scale CCS projects underperform or fail to meet their capture targets. As the new Production Gap Report points out, “the track record for CCS has been very poor to date, with around 80% of pilot projects over the last 30 years ending in failure.”

“The U.S. has been publicly subsidizing carbon capture projects since the early 1980s,” Rees of Oil Change International said during the November 14 Gas Exports Today media briefing. “We have over 40 years of evidence that it doesn’t work.”

The IEA and IPCC both recognize that carbon capture technologies have underperformed or made slower-than-expected progress. In its updated Net Zero roadmap report for example, the IEA states that “the history of [carbon capture] has largely been one of unmet expectations.” And in its Working Group III report on climate mitigation issued last year as part of the Sixth Assessment cycle, the IPCC cautions that CCS “currently faces technological, economic, institutional, ecological-environmental, and socio-cultural barriers” and notes that global deployment rates are “far below those in modeled pathways limiting global warming to 1.5°C or 2°C.”

Given this context, it is reasonable to doubt the promises made by carbon capture proponents. The numbers make it clear, as Climate Analytics’ Grant explained during the Production Gap Report launch event, that CCS and CDR technologies “are not going to be the solutions for cutting emissions in this critical decade.”

A new Global Witness analysis further substantiates this point. The organization calculated, based on petroleum production data from Rystad, that it would take the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) 340 years to capture the carbon it had produced from the company’s planned ramp up of oil and gas extraction between now and 2030. ADNOC is headed by Al Jaber, the controversial COP28 president, and new data shows the oil major’s planned output would result in the largest overshoot of the 1.5° C goal out of any fossil fuel company in the world. The Global Witness analysis also finds that even if ADNOC reaches the 10 million metric tons per year of CO2 capture by 2030, as it promises, that would result in mitigation of just two percent of the company’s projected 492 million metric tons of carbon emissions in 2030.

“If Al Jaber is serious – if we are serious – we must immediately reject the CCS false solution and tackle the existential oil and gas problem head on,” Global Witness’s Jonathan Noronha Gant said in a statement.

“CCS Is Not the Answer”

CCS critics also point to environmental, health, and safety risks that the technologies pose to communities where projects are targeted, which are often communities already overburdened by industrial pollution. Residents from these areas, such as the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coast, are voicing their opposition to the buildout of carbon capture in their communities.

“CCS is not the answer,” Roishetta Ozane, founder of the Vessel Project and resident of southwest Louisiana, said at the November 14 briefing. “We don’t need any more false solutions. We need real solutions with community voices and community input.”

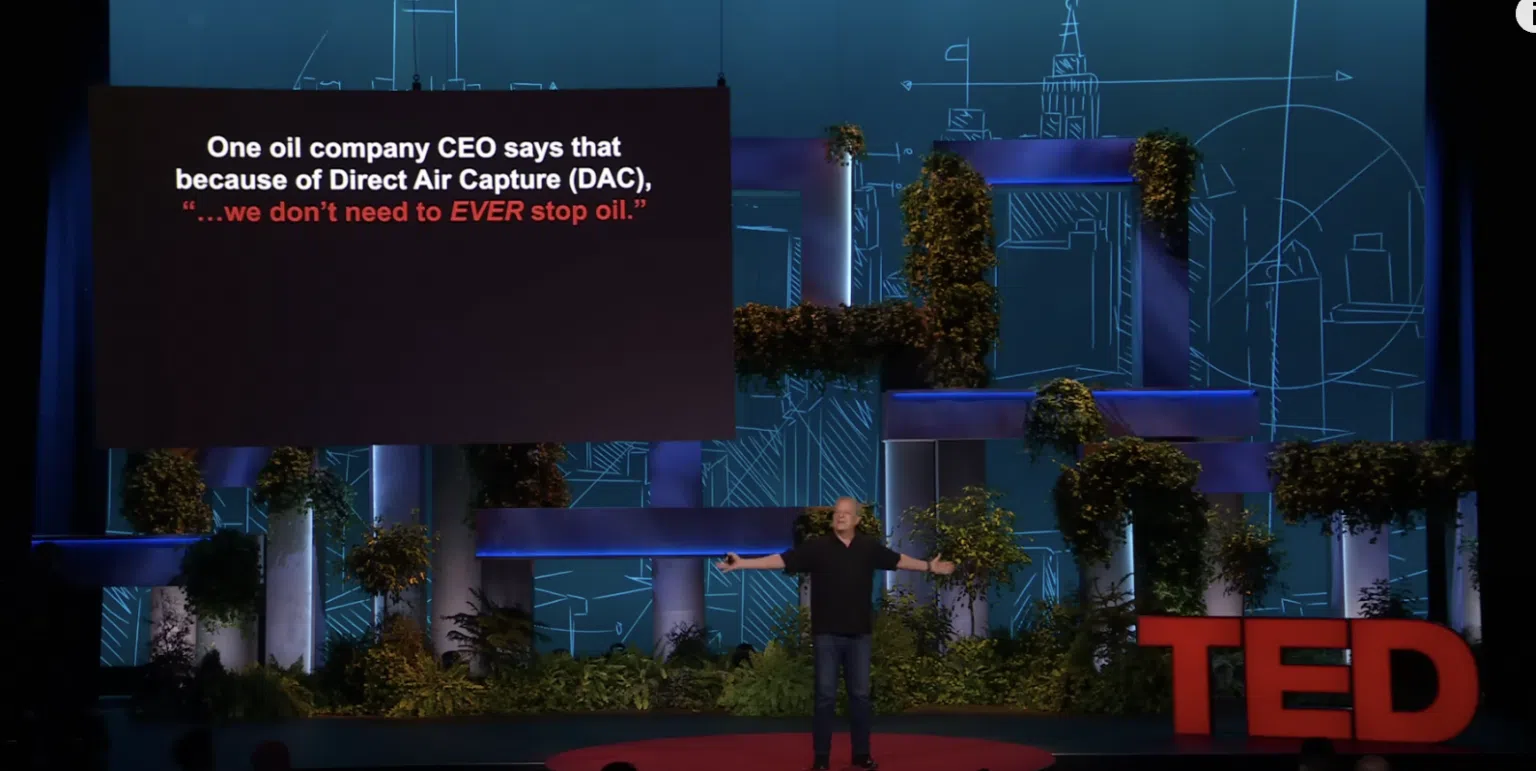

Ozane will be taking this message to COP28 in Dubai, where she will join other advocates on the frontlines of the fossil fuel and petrochemical industries’ expansion in calling for an end to this buildout and a phase out of fossil fuels. Competing with this call, however, is the narrative that emissions – not fossil fuels themselves – are the problem, and that it can be fixed through so-called “abatement” technologies – which provides cover for the continued production of coal, oil, and gas that is so clearly at odds with the rules of physics that govern the climate system.

During the Production Gap Report launch event, Grant emphasized that carbon capture technologies “do not replace the need for rapid and permanent reduction of fossil fuels.”

“And they therefore really can’t be used as a justification for continued expansion of fossil fuel extraction,” he added, “which is a narrative we’re seeing being pushed around the world, particularly as we come towards COP28.”

Original article by Dana Drugmand republished from DeSmog.