Andrew King, The University of Melbourne and Andrew Dowdy, The University of Melbourne

The run of extreme weather events around the world seems to be never-ending. After the northern summer of extreme heat and disastrous fires, we’ve seen more exceptional autumn weather over Europe with record-breaking heat in the UK.

Meanwhile, record-breaking rain and intense flash floods struck Greece before the same storm devastated Libya, with thousands dead.

Almost 20% of Africa is estimated to be in drought, and drought conditions are returning to parts of Australia. To top it off, we’ve seen several hurricanes intensify unusually quickly in the Atlantic.

We know climate change underpins some of the more extreme weather we’re seeing. But is it also pushing these extreme events to happen faster?

The answer? Generally, yes. Here’s how.

Flash droughts

We usually think of droughts as slowly evolving extreme events which take months to form.

But that’s no longer a given. We’ve seen some recent droughts develop unexpectedly quickly, giving rise to the phrase “flash drought”.

How does this happen? It’s when a lack of rainfall in a region combines with high temperatures and sunny conditions with low humidity. When these conditions are in place, it increases how much moisture the atmosphere is trying to pull from the land through evaporation. The end result: faster drying-out of the ground.

Flash droughts tend to be short, so they don’t tend to cause the major water shortages or dry river beds we’ve seen during long droughts in parts of Australia and South Africa, for example. But they can cause real problems for farmers. Farmers in parts of eastern Australia are already grappling with the sudden return of drought after three years of rainy La Niña conditions.

As we continue to warm the planet, we’ll see more flash droughts and more intense ones. That’s because dry conditions will more often coincide with higher temperatures as relative humidity falls across many land regions.

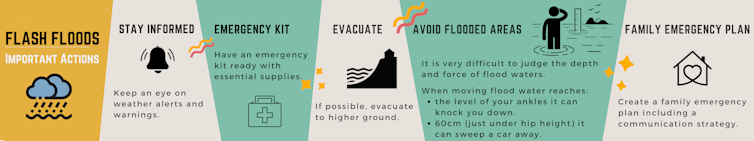

Flash floods and extreme rainfall

Climate change can cause increased rainfall variability. Some parts of the world will get a lot wetter, on average, while others will get drier, increasing the variation in rainfall between different regions. For Australia, most locations are generally expected to have intensified downpours of rain, as well as intensified droughts. So we might be saying more often “it doesn’t rain, it pours!”.

We’re seeing exceptionally extreme rainfall in many recent events. The recent floods that submerged villages in Greece came from a sudden downpour of over 500 millimetres in a single day. Hong Kong was hit last week by the heaviest rains in 140 years, flooding subway stations and turning streets into rivers.

But why does it happen so quickly?

Sudden extreme rains fall when we have very moist air coupled with a weather system that forces air to rise.

We’ve long known human-caused climate change is increasing how much moisture the air can hold generally, rising by about 7% per degree of global warming. That means storms now have the potential to hold and dump more water.

Notably, the impact of climate change on rain-bearing weather systems can vary by region, which makes the picture more complicated. That means, for instance, climate change may lead to more extreme rain in some places, while other places may only see an intensification in really short extreme rain events and not for longer timescales.

We can safely say, though, that in most parts of the world, we’re seeing more intense storms and sudden extreme rainfall. Sudden dumps of rain drive flash floods.

More moisture in the air helps fuel more intense convection, where warm air masses rise and form clouds. In turn, this can trigger efficient, quick and intense dumps of rain from thunderstorms.

These short-duration rain events can be much larger than you’d expect from the 7% increase in moisture per degree of warming.

Flash cyclones? Hurricanes are intensifying faster

Last month, Hurricane Idalia caused major flooding in Florida. As we write, Hurricane Lee is approaching the US.

Both tropical storms had something odd about them – unusually rapid intensification. That is, they got much stronger in a short period of time.

Usually, this process might increase wind speeds by about 50 kilometres per hour over a 24-hour period for a hurricane – also known as tropical cyclones and typhoons. But Lee’s wind speeds increased by 129km/h over that period. US meteorological expert Marshall Shepherd has dubbed the phenomenon “hyperintensification”, which could put major population centres at risk.

Rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones are strong and can be very hazardous, but they aren’t very common. To trigger them, you need a combination of very high sea surface temperatures, moist air and wind speeds that don’t change much with height.

While still uncommon, rapid intensification is potentially getting more frequent as we heat the planet. This is because oceans have taken up so much of the heat and there’s more moisture in the air. There’s much more still to learn here.

Australia’s El Niño summer in a warming world

Spring and summer in Australia are likely to be warmer and drier than usual. This is due to the El Niño climate cycle predicted for the Pacific Ocean. If, as predicted, we also get a positive Indian Ocean Dipole event, this can heighten the hotter, drier weather brought by El Niño. After three wet La Niña years, this is likely to be a marked shift.

If it arrives as expected, El Niño would lower the risk of tropical cyclones for northern Australia and reduce chances of heavy rain across most of the continent.

But for farmers, it may help trigger flash droughts. Prevailing warm and dry conditions may rapidly dry the land and reduce crop yields and slow livestock growth.

Drier surfaces coupled with grass growth from the wet years could worsen fire risk. Grass can dry out much faster than shrubs or trees, and grass fires can start and spread very rapidly.

Climate change loads the dice for extreme weather. And as we’re now seeing, these extremes aren’t just more intense – they can happen remarkably fast.

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne and Andrew Dowdy, Principal Research Scientist, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.