95 UK Universities That Have Pledged to Divest from Oil and Gas Use Banks Funding Climate Crisis

Original article by Max Colbert republished from DeSmog

Students have accused the institutions of ‘hypocritical and performative’ green commitments.

Almost 100 universities that have pledged to shed ties to the fossil fuel industry still bank with financial institutions that have collectively provided $419 billion (£345 billion) to polluting interests between 2016 and 2022.

The new research, conducted by campaign group Make My Money Matter and obtained using Freedom of Information requests, shows that 95 universities still hold a bank account with one of five leading global fossil fuel funders: Barclays, HSBC, Santander, NatWest, and Lloyds.

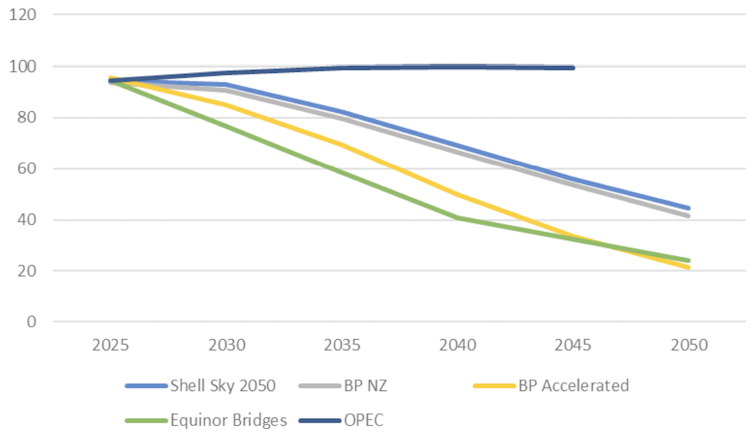

These banks have supplied billions in financing to Shell and BP, which this year scaled back their climate targets, as well as to other oil and gas firms such as ExxonMobil and TotalEnergies. Barclays was the bank of choice, used by nearly three quarters (73 percent) of the universities.

Barclays was the largest European financier of fossil fuels between the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2016, which set a goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C, and 2022. The British bank propped up the oil and industry with $190.5 billion (£157 billion) in funding during this time, according to the annual Banking on Climate Chaos report from the climate campaign group Rainforest Action Network (RAN).

This story comes after DeSmog revealed earlier this month that UK universities have accepted £40.4 million in funding from fossil fuel companies since 2022. Students across Europe have protested at schools and universities since returning for the new academic year. In the UK, activists from Just Stop Oil have renewed their campaigning on campuses, targeting University College London, Birmingham, Sussex, Falmouth, and Exeter.

Over 100 universities across the UK, representing 65 percent of the higher education sector, have pledged to divest from the fossil fuel industry since 2014. Over 50 are yet to make any public commitments.

Make My Money Matter says that it will be writing to universities and calling on them to ensure that their divestment commitments are not being undone by their banking choices.

“Divesting from fossil fuels while banking with Barclays is hypocritical and performative,” said Jo Campling, welfare and sustainability officer at Sheffield University Students’ Union. “Universities claim they are striving for a better future by educating their students yet they continue to provide legitimacy to the financial institutions ignoring universities’ own scientists and driving us ever closer to irreversible climate breakdown.”

‘More Needs to be Done’

The universities that have held accounts with Barclays include Bristol, one of the “greenest universities in the UK”, University College London (UCL), the UK’s largest higher education institution by student population, and the University of Glasgow, the first UK university to commit to fossil fuel divestment.

Researchers analysed the period between April 2021 and April 2023. The threshold for a ‘banking relationship’ includes a current or deposit account held within the period, but excludes other services such as loans, credit facilities, or currency exchanges.

In 2022, Barclays was a major backer of unconventional oil projects, such as Arctic extraction and extraction from tar sands. The latter emits up to three times more global warming pollution than producing the same quantity of crude oil.

As of late 2022, following pressure from investors, Barclays has agreed to scale down its financing of oil sands operations. However, the new research shows both Barclays and HSBC remained among the top 10 (seven and eight respectively) global financiers of new fossil fuel expansion projects.

Barclays is facing heavy criticism for its ongoing role in facilitating climate breakdown, and its annual general meeting in May was disrupted by climate activists from Extinction Rebellion.

A spokesperson for Barclays told DeSmog: “Aligned to our ambition to be a net zero bank by 2050, we believe we can make the greatest difference by working with our clients as they transition to a low-carbon business model, reducing their carbon-intensive activity whilst scaling low-carbon technologies, infrastructure and capacity.

“We have set 2030 targets to reduce the emissions we finance in five high-emitting sectors, including the energy sector, where we have achieved a 32 percent reduction since 2020. In addition, to scale the needed technologies and infrastructure, we have provided £99 billion of green finance since 2018, and have a target to facilitate $1 trillion in sustainable and transition financing between 2023 and 2030.”

Peter Vermeulen, chief financial officer at the University of Bristol told DeSmog that the university takes its “climate commitments seriously” and engages with major suppliers, including banks, “to see where positive improvements and changes can be made”.

Vermeulen added that, “I, like many others, am disappointed in Barclays’s climate performance, and that they only put a serious climate plan in place in 2020. In my previous role I actively engaged with Barclays on their lack of progress in this area and witnessed improvement. More needs to be done and for that reason, since joining the University of Bristol this summer, I will step that up even further, with university, staff, and student representatives involved in this.”

Rainforest Action Network has calculated that the world’s biggest banks poured $673 billion (£554 million) into fossil fuels in 2022, while DeSmog revealed in May that four in five bank directors at the six largest banks in the U.S. have ties to polluting companies and organisations, including major fossil fuel firms.

Commenting on the findings of the Make My Money Matter report, Nat Gorodnitski from Students Organising for Sustainability said: “If we want to stop the worst effects of climate change, we need to end fossil fuel funding. Banks are the biggest funders by a long way and rely heavily on the higher education sector for recruitment, reputation, and business, while their fossil fuel financing contradicts academic research, university policies, and students’ needs.

“This gives students and universities the unique power to pressure banks to end their fossil fuel financing in a meaningful way, and call for a shift to funding sustainable energy.”

A spokesperson for HSBC said: “Supporting the transition to net zero and engaging with clients to help them diversify and decarbonise is critically important to us. We are committed to aligning our financed emissions to net zero by 2050.”

A University of Glasgow spokesperson that the university “is committed to doing our part to tackle the climate emergency. In 2014, we pledged to divest our holdings in companies involved in the oil and gas sectors over a 10 year period, and have already achieved this. We have also set an ambitious target to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Our socially responsible investment policy is regularly reviewed.”

Original article by Max Colbert republished from DeSmog