Analysis: The climate papers most featured in the media in 2025

Original article republished from Carbon Brief under a CC license.

The year 2025 saw the return to power of Donald Trump, a jewellery heist at the Louvre museum in Paris and an engagement that “broke the internet”.

Amid the biggest stories of the year, climate change research continued to feature prominently in news and social media feeds.

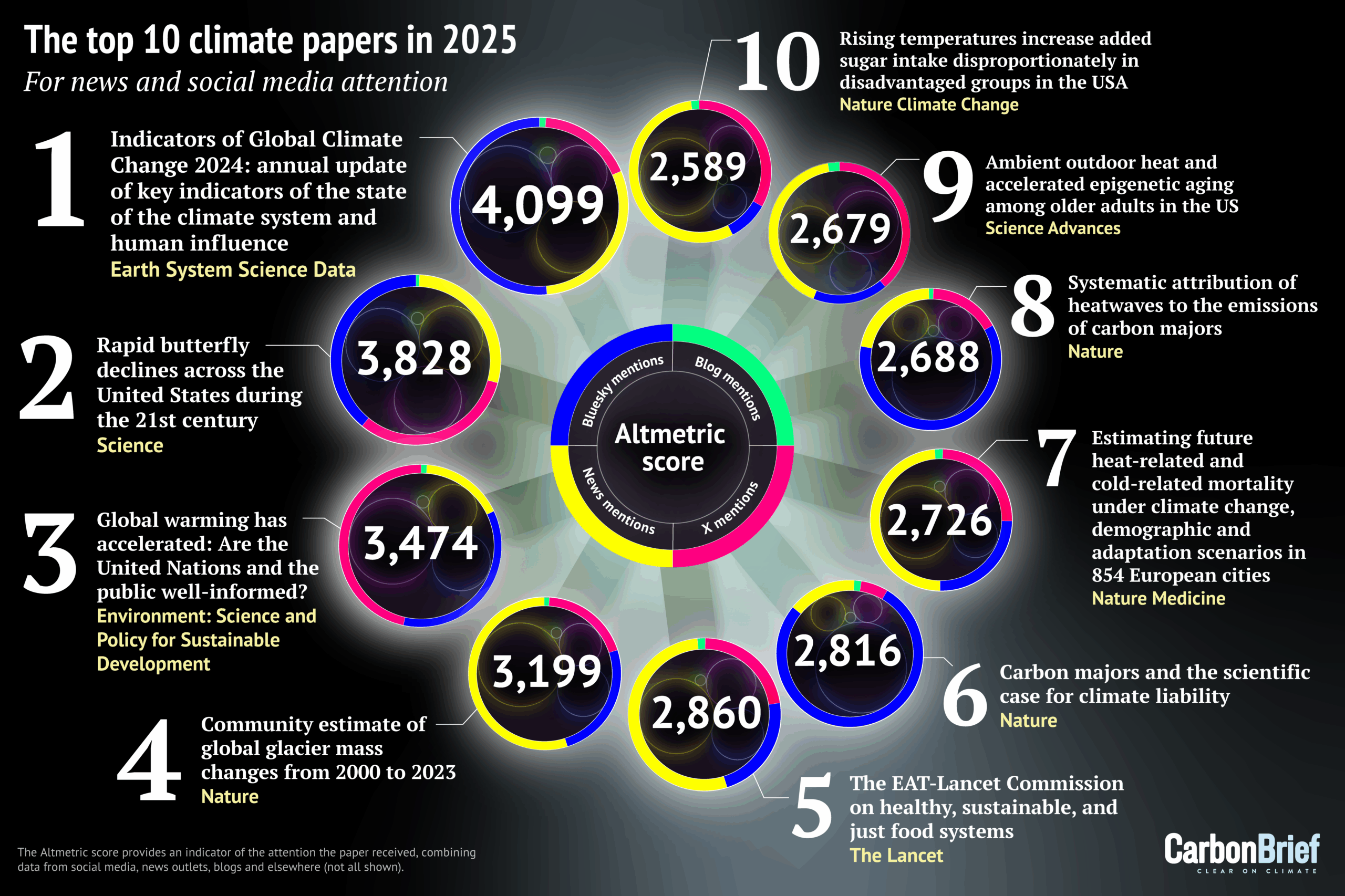

Using data from Altmetric, which scores research papers according to the attention they receive online, Carbon Brief has compiled its annual list of the 25 most talked-about climate-related studies of the past year.

The top 10 – shown in the infographic above and list below – include research into declining butterflies, heat-related deaths, sugar intake and the massive loss of ice from the world’s glaciers:

- Indicators of Global Climate Change 2024: annual update of key indicators of the state of the climate system and human influence

- Rapid butterfly declines across the US during the 21st century

- Global warming has accelerated: Are the UN and the public well informed?

- Community estimate of global glacier mass changes from 2000 to 2023

- The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable and just food systems

- Carbon majors and the scientific case for climate liability

- Estimating future heat-related and cold-related mortality under climate change, demographic and adaptation scenarios in 854 European cities

- Systematic attribution of heatwaves to the emissions of carbon majors

- Ambient outdoor heat and accelerated epigenetic aging among older adults in the US

- Rising temperatures increase added sugar intake disproportionately in disadvantaged groups in the US

Later in this article, Carbon Brief looks at the rest of the top 25 and provides analysis of the most featured journals, as well as the gender diversity and country of origin of authors.

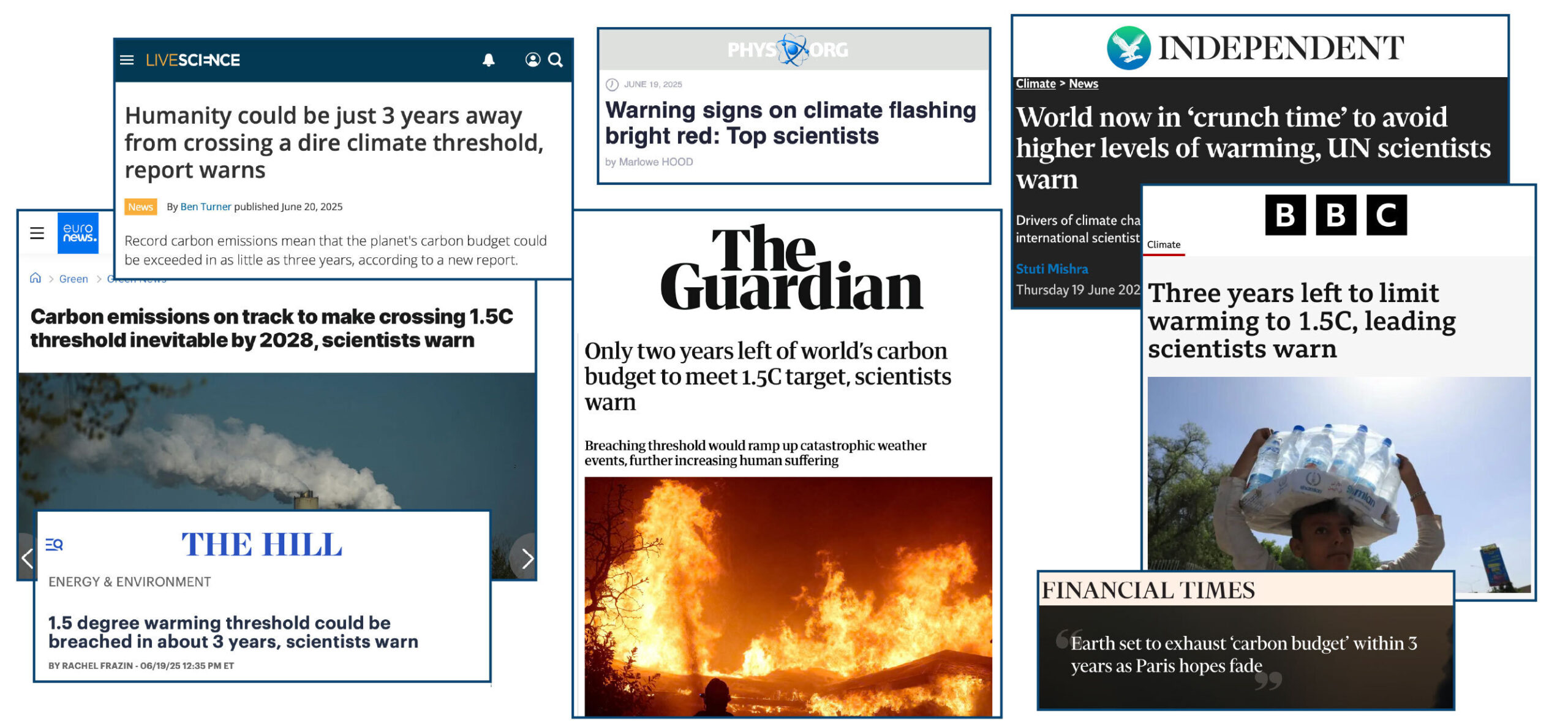

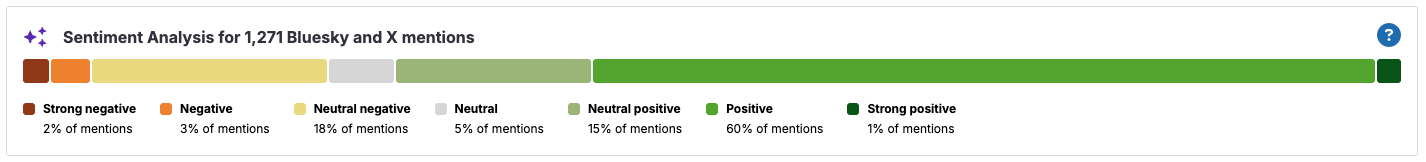

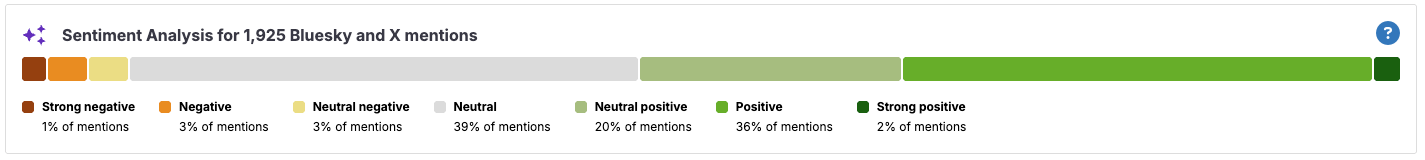

New for this year is the inclusion of Altmetric’s new “sentiment analysis”, which scores how positive or negative a paper’s social media attention has been.

(For Carbon Brief’s previous Altmetric articles, see the links for 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 and 2015.)

Global indicators

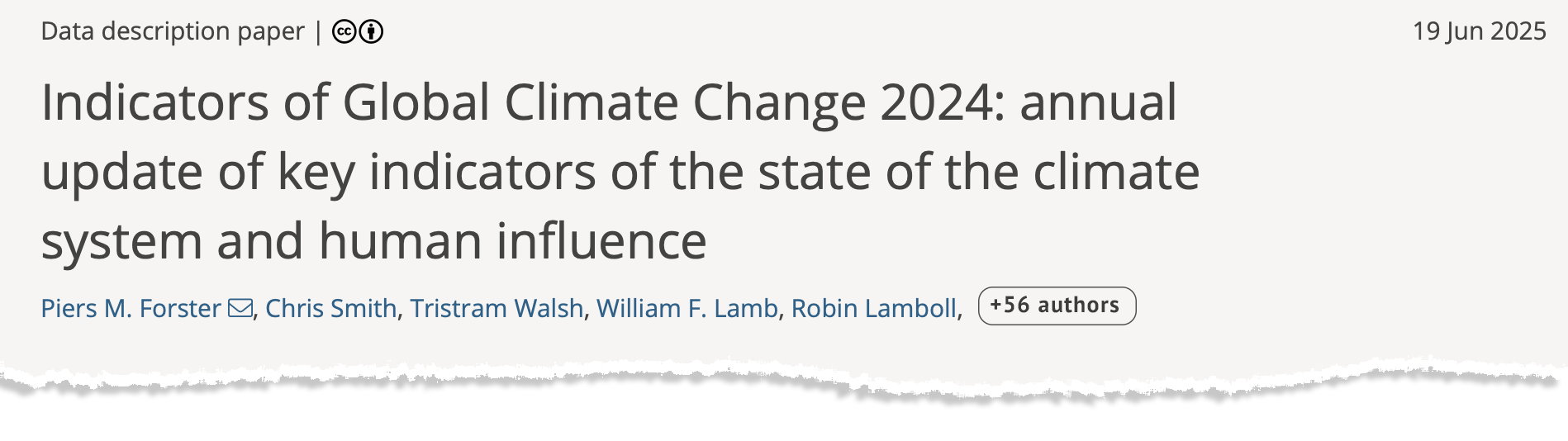

The top-scoring climate paper of 2025, ranking 24th of any research paper on any topic, is the annual update of the “Indicators of Global Climate Change” (IGCC) report.

The report was established in 2023 to help fill the gap in climate information between assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which can take up to seven years to complete. It includes the latest data on global temperatures, the remaining carbon budget, greenhouse gas emissions and – for the first time – sea level rise.

The paper, published in Earth System Science Data, has an Altmetric score of 4,099. This makes it the lowest top-scoring climate paper in Carbon Brief’s list since 2017.

(An Altmetric score combines the mentions that published peer-reviewed research has received from online news articles, blogs, Wikipedia and on social media platforms such as Facebook, Reddit, Twitter and Bluesky. See an earlier Carbon Brief article for more on how Altmetric’s scoring system works.)

Previous editions of the IGCC have also appeared in Carbon Brief’s list – the 2024 and 2023 iterations ranked 17th and 18th, respectively.

This year’s paper was mentioned 556 times in online news stories, including in the Associated Press, Guardian, Independent, Hill and BBC News.

Many outlets led their coverage with the study’s findings on the global “carbon budget”. This warned that the remaining carbon budget to limit warming to 1.5C will be exhausted in just three years if global emissions continue at their current rate.

In a Carbon Brief guest post about the study, authors Prof Piers Forster and Dr Debbie Rosen from the University of Leeds wrote:

“It is also now inevitable that global temperatures will reach 1.5C of long-term warming in the next few years unless society takes drastic, transformative action…Every year of delay brings reaching 1.5C – or even higher temperatures – closer.”

Forster, who was awarded a CBE in the 2026 new year honours list, tells Carbon Brief that media coverage of the study was “great” at “putting recent extreme weather in the context of rapid long-term rates of global warming”.

However, he adds:

“Climate stories are not getting the coverage they deserve or need at the moment so the community needs to get all the help we can for getting clear consistent messages out there.”

The paper was tweeted more than 300 times and posted on Bluesky more than 950 times. It also appeared in 22 blogs.

Using AI, Altmetric now analyses the “sentiment” of this social media attention. As the summary figure below shows, the posts about this paper were largely positive, with an approximate 3:1 split of positive and negative attention.

Butterfly decline

With an Altmetric score of 3,828, the second-highest scoring climate paper warns of “widespread” declines in butterfly numbers across the US since the turn of the century.

The paper, titled “Rapid butterfly declines across the US during the 21st century” and published in Science, identifies a 22% fall in butterfly numbers across more than 500 species between 2000 and 2020.

(There is a higher-scoring paper, “The 2025 state of the climate report: a planet on the brink”, in the journal BioScience, but it is a “special report” and was not formally peer reviewed.)

The scale of the decline suggests “multiple and broadly acting threats, including habitat loss, climate change and pesticide use”, the paper says. The authors find that “species generally had stronger declines in more southerly parts of their ranges”, with some of the most negative trends in the driest and “most rapidly warming” US states.

The research was covered in 560 news articles, including the New York Times, Guardian, Associated Press, NPR, El País and BBC News. Much of the news coverage led with the 22% decline figure.

The paper was also mentioned in 13 blogs, more than 750 Bluesky posts and more than 600 tweets.

The sentiment analysis reveals that social media posts about the paper were largely negative. However, closer inspection reveals that this negativity is predominantly towards the findings of the paper, not the research itself.

For example, a Bluesky post on the “distressing” findings by one of the study’s authors is designated as “neutral negative” by Altmetric’s AI analysis.

In a response to a query from Carbon Brief, Altmetric explains that the “goal is to measure how people feel about the research paper itself, not the topic it discusses”. However, in some cases the line can be “blurred” as the AI “sometimes struggles to separate the subject matter from the critique”. The organisation adds that it is “continuously working on improving our models to better distinguish between the post’s content and the research output”.

On the attention that the paper received, lead author Dr Collin Edwards of the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife says that “first and foremost, people care about butterflies and our results are broad-reaching, unequivocal and, unfortunately, very concerning”.

Edwards tells Carbon Brief he hopes the clarity of the writing made the paper accessible to readers, noting that he and his co-authors “sweat[ed] over every word”.

The resulting news coverage “accurately captured the science”, Edwards says:

“Much as I wish our results were less consistently grim, the consistency and simplicity of our findings mean that even if a news story only provides the highest level summary, it isn’t misleading readers by skipping some key caveat or nuance that changes the interpretation.”

Warming ‘acceleration’

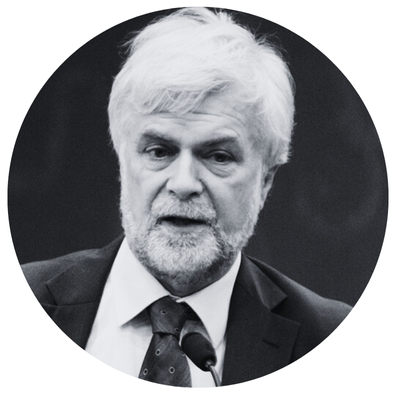

In third place in Carbon Brief’s list for 2025 is the latest scientific paper from veteran climatologist Dr James Hansen, former director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and now adjunct professor at Columbia University’s Earth Institute.

The paper, titled “Global warming has accelerated: Are the UN and the public well-informed?” was published in the journal Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. It generated an Altmetric score of 3,474.

The study estimates that the record-high global temperatures in the last few years were caused by a combination of El Niño and a reduction in air pollution from international shipping.

The findings suggest that the cooling effect of aerosols – tiny, light‑scattering particles produced mainly by burning fossil fuels – has masked more of the warming driven by greenhouse gases than previously estimated by the IPCC.

As efforts to tackle air pollution continue to reduce aerosol emissions, warming will accelerate further – reaching 2C by 2045, according to the research.

The paper was covered by almost 400 news stories – driven, in part, by Hansen’s comments in a press briefing that the Paris Agreement’s 2C warming limit was already “dead”.

Hansen’s analysis received a sceptical response from some scientists. For example, Dr Valerie Masson-Delmotte, an IPCC co-chair for its most recent assessment report on climate science, told Agence France-Presse the research “is not published in a climate science journal and it formulates a certain number of hypotheses that are not consistent with all the available observations”.

In addition, other estimates, including by Carbon Brief, suggest new shipping regulations have made a smaller contribution to warming than estimated by Hansen.

Hansen tells Carbon Brief that the paper “did ok” in terms of media coverage, although notes “it’s on [scientists] to do a better job of making clear what the core issues are in the physics of climate change”.

With more than 1,000 tweets, the paper scored highest in the top 25 for posts on Twitter. It was also mentioned in more than 800 Bluesky posts and on 27 blogs.

The sentiment analysis suggests that these posts were largely positive, with just a small percentage of negative comments.

Making the top 10

Ranking fourth in Carbon Brief’s analysis is a Nature paper calculating changes in global glacier mass over 2000-23. The study finds glaciers worldwide lost 273bn tonnes of ice annually over that time – with losses increasing by 36% between 2000-11 and 2012-23.

The study has an Altmetric score of 3,199. It received more news coverage than any other paper in this year’s top 25, amassing 1,187 mentions. with outlets including the Guardian, Associated Press and Economic Times.

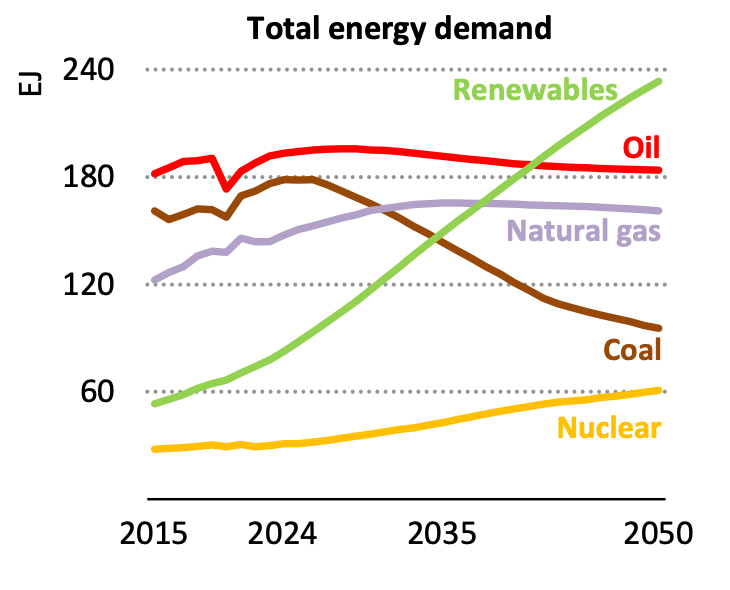

At number five, with an Altmetric score of 2,860, is the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable and just food systems.

Carbon Brief’s coverage of the report highlights that “a global shift towards ‘healthier’ diets could cut non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions, such as methane, from agriculture by 15% by 2050”. It adds:

“The findings build on the widely cited 2019 report from the EAT-Lancet Commission – a group of leading experts in nutrition, climate, economics, health, social sciences and agriculture from around the world.”

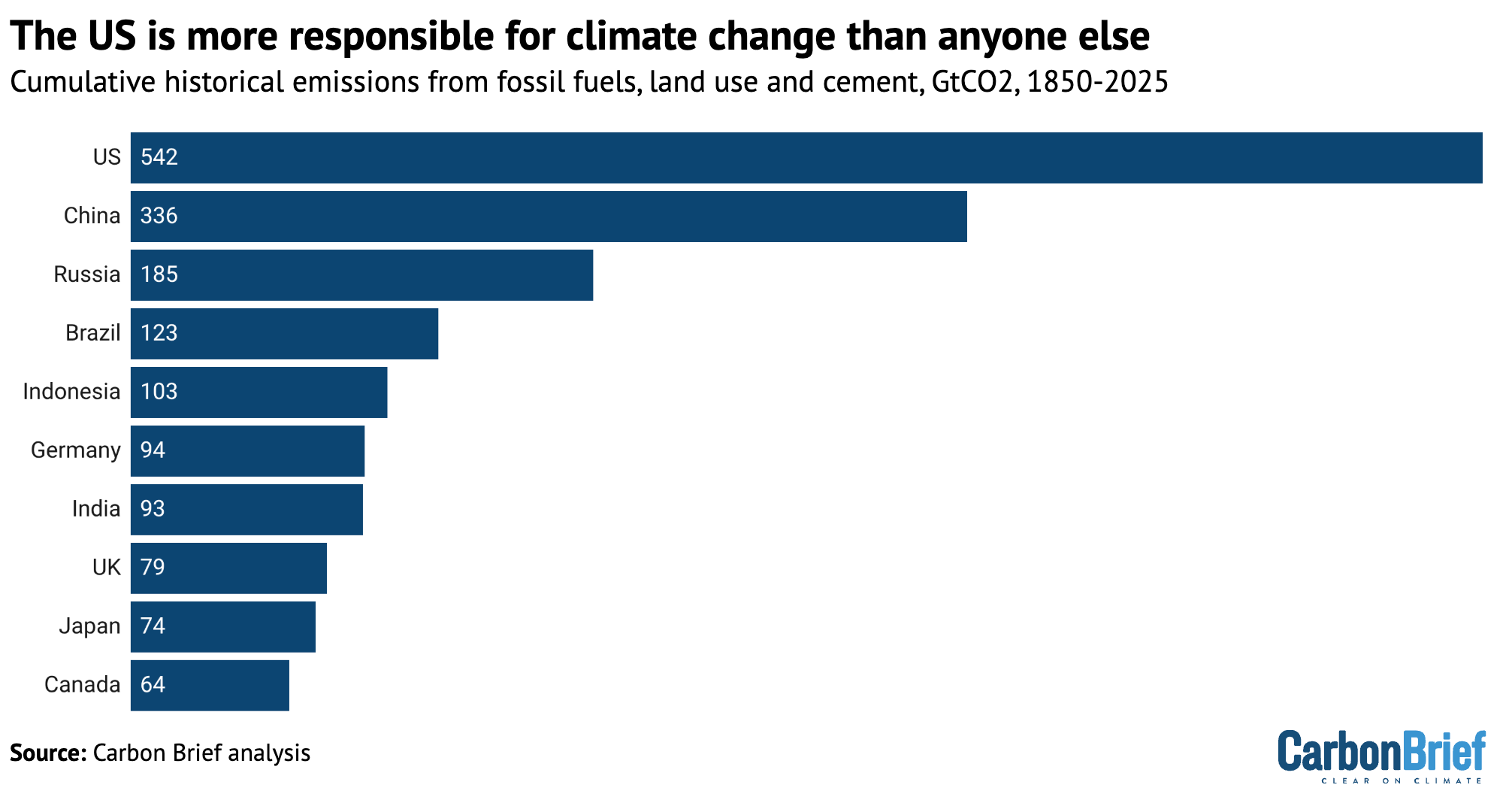

Also making the top 10 – ranking sixth and eighth – are a pair of papers published in Nature, which both link extreme heat to the emissions of specific “carbon majors” – large producers of fossil fuels, such as ExxonMobil, Shell and Saudi Aramco,.

The first is a perspective, titled “Carbon majors and the scientific case for climate liability”, published in April. It begins:

“Will it ever be possible to sue anyone for damaging the climate? Twenty years after this question was first posed, we argue that the scientific case for climate liability is closed. Here we detail the scientific and legal implications of an ‘end-to-end’ attribution that links fossil fuel producers to specific damages from warming.”

The authors find “trillions (of US$) in economic losses attributable to the extreme heat caused by emissions from individual companies”.

The paper was mentioned 1,329 times on Bluesky – the highest in this year’s top 25. It was also mentioned in around 270 news stories.

Published four months later, the second paper uses extreme event attribution to assess the impact of climate change on more than 200 heatwaves recorded since the year 2000.

The authors find one-quarter of the heatwaves would have been “virtually impossible” without human-caused global warming. They add that the heatwaves were, on average, 1.7C hotter due to climate change, with half of this increase due to emissions stemming from the operations and production of carbon majors.

This study was mentioned in almost 300 news stories – including by Carbon Brief – as well as 222 tweets and 823 posts on Bluesky.

In seventh place is a Nature Medicine study, which quantifies how heat-related and cold-related deaths will change over the coming century as the climate warms.

A related research briefing explains the main findings of the paper:

“Heat-related deaths are estimated to increase more rapidly than cold-related deaths are estimated to decrease under future climate change scenarios across European cities. An unrealistic degree of adaptation to heat would be required to revert this trend, indicating the need for strong policies to reduce greenhouse gases emissions.”

The paper was mentioned 345 times in the news, including in the Financial Times, New Scientist, Guardian and Bloomberg.

The paper in ninth place also analyses the health impacts of extreme heat. The study, published in Science Advances, finds that extreme heat can speed up biological ageing in older people.

Rounding out the top 10 is a Nature Climate Change study, titled “Rising temperatures increase added sugar intake disproportionately in disadvantaged groups in the US”.

The study finds that at higher temperatures, people in the US consume more sugar – mainly due to “higher consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and frozen desserts”. The authors project that warming of 5C would drive additional sugar consumption of around 3 grams per day, “with vulnerable groups at an even higher risk”.

Elsewhere in the top 25

The rest of the top 25 includes a wide range of research, from “glacier extinction” and wildfires to Amazon drought and penguin guano.

In 13th place is a Nature Climate Change study that finds the wealthiest 10% of people – defined as those who earn at least €42,980 (£36,605) per year – contributed seven times more to the rise in monthly heat extremes around the world than the global average.

The authors also explore country-level emissions, finding that the wealthiest 10% in the US produced the emissions that caused a doubling in heat extremes across “vulnerable regions” globally.

(See Carbon Brief’s coverage of the paper for more details.)

In 15th place is the annual Lancet Countdown on health and climate change – a lengthy report with more than 120 authors.

The study warns that “climate change is increasingly destabilising the planetary systems and environmental conditions on which human life depends”.

This annual analysis from the Lancet often features in Carbon Brief’s top 25 analysis. After three years in the Carbon Brief’s top 10 over 2020-23, the report landed in 20th place in 2023 and missed out on a spot in the top 25 altogether in 2024.

In 16th place is a Science Advances study, titled “Increasing rat numbers in cities are linked to climate warming, urbanisation and human population”. The study uses public complaint and inspection data from 16 cities around the world to estimate changes in rat populations.

It finds that “warming temperatures and more people living in cities may be expanding the seasonal activity periods and food availability for urban rats”.

The study received 320 new mentions, including in the Washington Post, New Scientist and National Geographic.

In 21st place is a Nature Climate Change paper, titled “Peak glacier extinction in the mid-21st century”. The study authors “project a sharp rise in the number of glaciers disappearing worldwide, peaking between 2041 and 2055 with up to ~4,000 glaciers vanishing annually”.

Completing the top 25 is a Nature study on the “prudent planetary limit for geological carbon storage” – where captured CO2 is injected deep underground, where it can stay trapped for thousands of years.

In a Carbon Brief guest post, study authors Dr Matthew Gidden and Prof Joeri Rogelj explain that carbon dioxide removal will only be effective at limiting global temperature rise if captured CO2 is injected “deep underground, where it can stay trapped for thousands of years”.

The guest post warns that “geological carbon storage is not limitless”. It states that “if all available safe carbon storage capacity were used for CO2 removal, this would contribute to only a 0.7C reduction in global warming”.

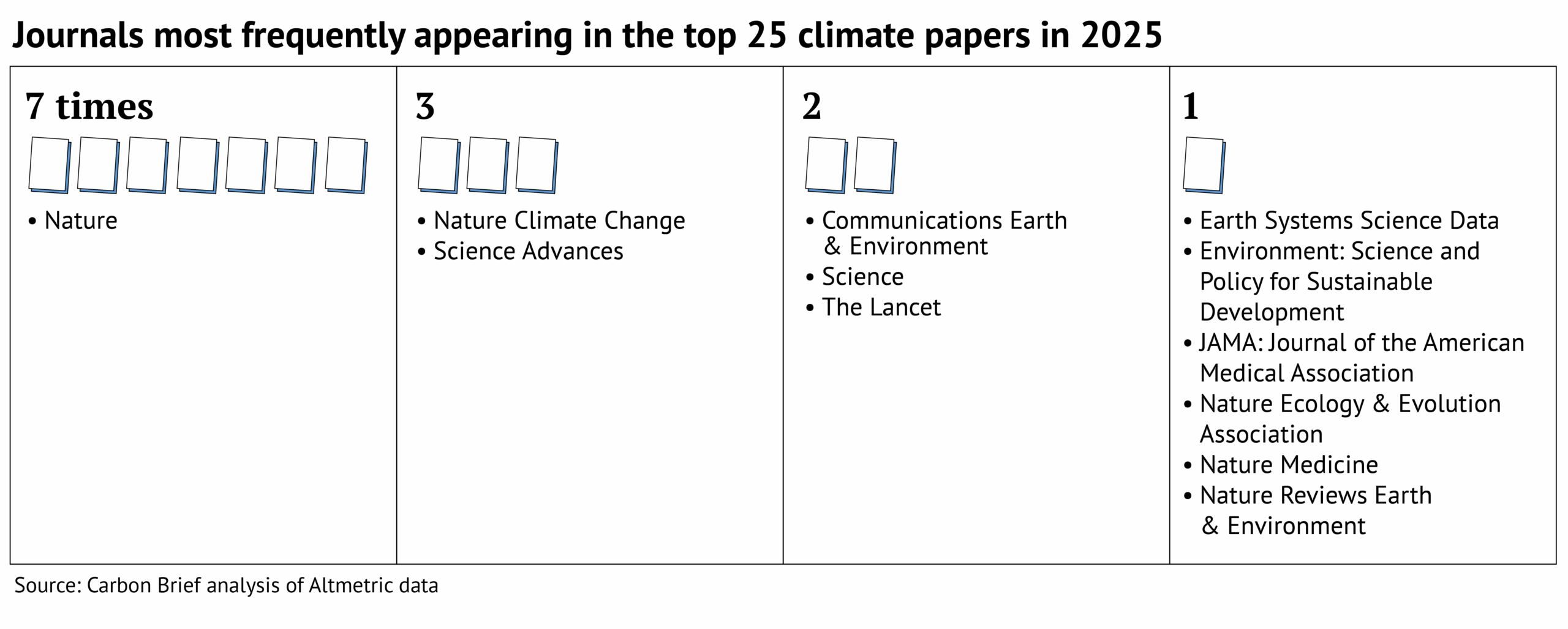

Top journals

The journal Nature dominates Carbon Brief’s top 25, with seven papers featured.

Many other journals in the Springer Nature stable also feature, including Nature Climate Change (three), Communications Earth & Environment (two), as well as Nature Ecology & Evolution, Nature Medicine and Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (one each).

Also appearing more than once in the top 25 are Science Advances (three), Science (two) and the Lancet (two).

This is shown in the graphic below.

All the final scores for 2025 can be found in this spreadsheet.

Diversity in the top 25

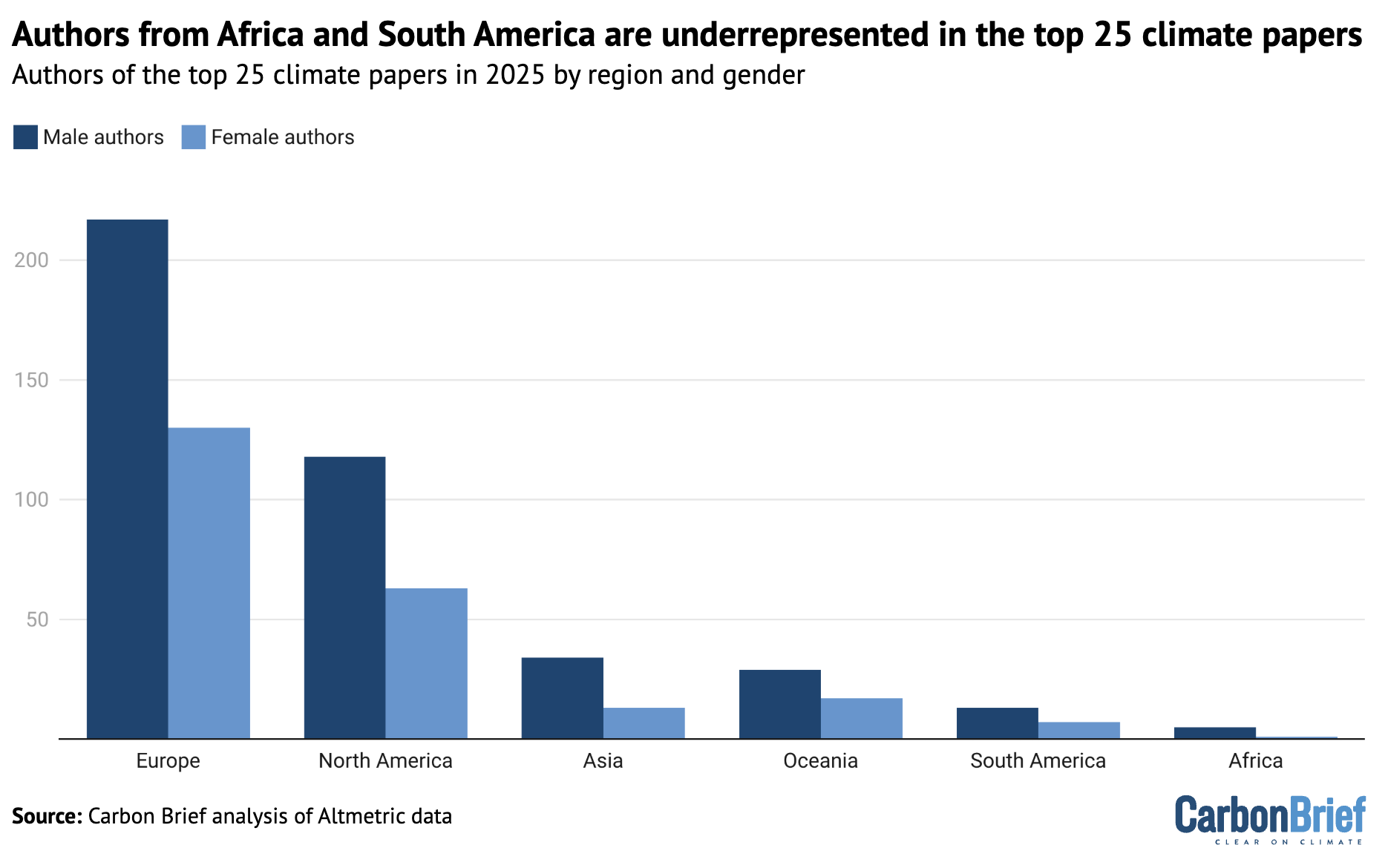

The top 25 climate papers of 2025 cover a huge range of topics and scope. However, analysis of their authors reveals a distinct lack of diversity.

In total, the top 25 includes more than 650 authors – the highest number since Carbon Brief began this analysis in 2022.

This is largely due to a few publications with an exceptionally high number of authors. For example, the 2025 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change has almost 130 authors alone, accounting for almost one-fifth of authors in this analysis.

Carbon Brief recorded the gender and country of affiliation for each of these authors. (The methodology used was developed by Carbon Brief for analysis presented in a special 2021 series on climate justice.)

The analysis reveals that 88% of the authors of the climate papers most featured in the media in 2025 are from institutions in the global north.

Global South: The “global south” is a term used to broadly describe lower-income countries in regions such as Africa, Asia and Latin America. It is often used to denote nations that are either in… Read More

Carbon Brief defines the global north as North America, Europe, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. It defines the global south as Asia (excluding Japan), Africa, Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand), Latin America and the Caribbean.

The analysis shows that 53% of authors are from European institutions, while only 1% of authors are from institutions in Africa.

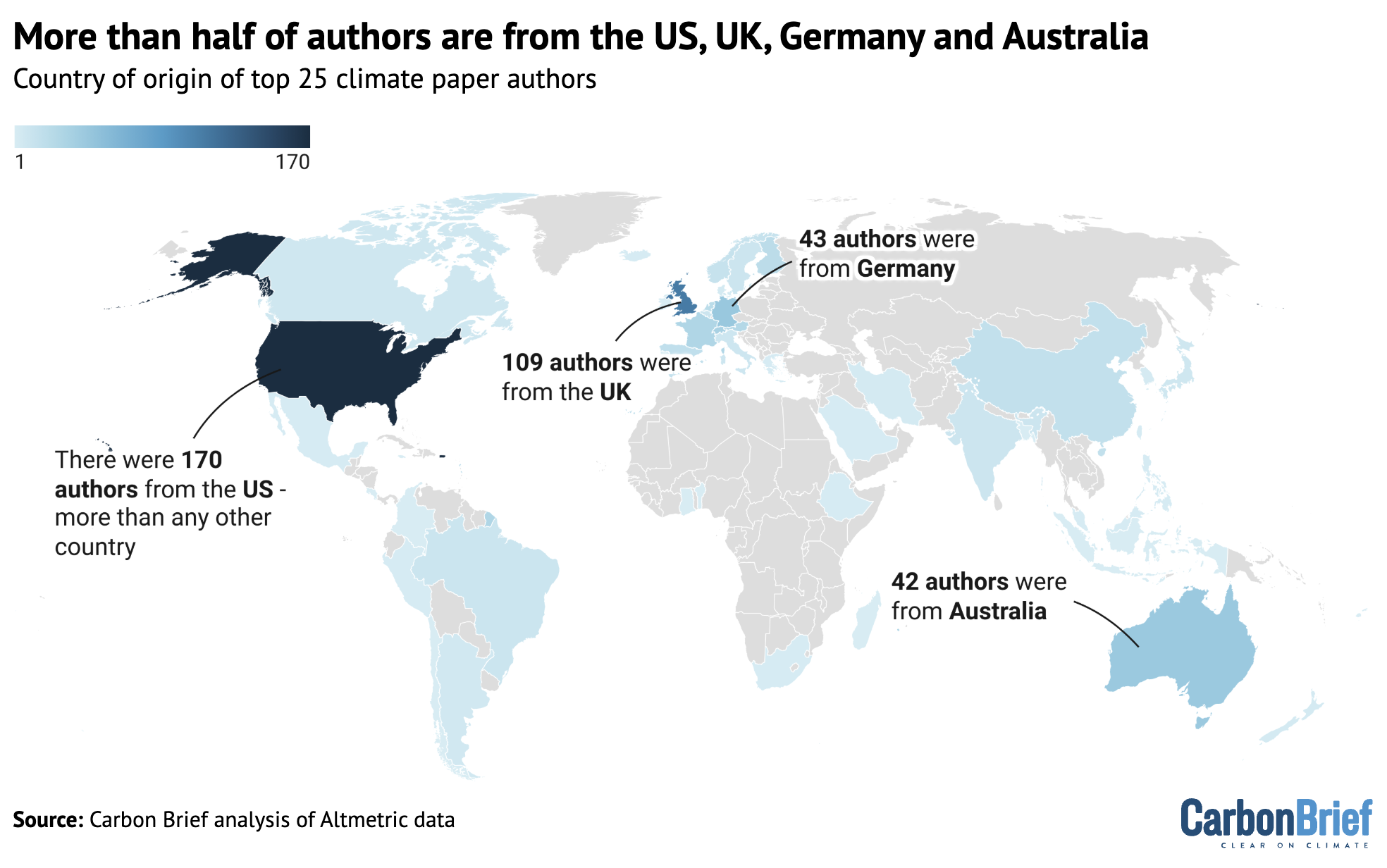

Further data analysis shows that there are also inequalities within continents. The map below shows the percentage of authors from each country, where dark blue indicates a higher percentage. Countries that are not represented by any authors in the analysis are shown in grey.

The top-ranking countries on this map are the US and the UK, which account for 26% and 16% of the authors, respectively.

Carbon Brief also analysed the gender of the authors.

Only one-third of authors from the top 25 climate papers of 2025 are women and only five of the 25 papers list a woman as lead author.

The plot below shows the number of authors from each continent, separated into men (dark blue) and women (light blue).

The full spreadsheet showing the results of this data analysis can be found here. For more on the biases in climate publishing, see Carbon Brief’s article on the lack of diversity in climate-science research.

- Media reaction: The 2025 Texas floods and the role of climate change

- Q&A: What we do – and do not – know about the blackout in Spain and Portugal

- Analysis: The climate papers most featured in the media in 2024

- Media reaction: The 2025 Los Angeles wildfires and the role of climate change

Original article republished from Carbon Brief under a CC license.